Last December, an explosive documentary series premiered on Netflix: Making a Murderer. The show explores the story of Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man who had been wrongfully convicted of sexual assault and attempted murder and served 18 years in prison before being fully exonerated by DNA evidence. Two years after his release, however, Avery was arrested again on murder charges, as was his nephew, sixteen-year-old Brendan Dassey.

Over ten episodes, Making a Murderer documented instance after instance of egregious prosecutorial and law enforcement misconduct.

On August 12, 2016, a federal judge issued a 91-page decision which granted Dassey's petition for a writ of habeas corpus and overturned his convictions, holding that Dassey's "confession" was involuntary and contrary to the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

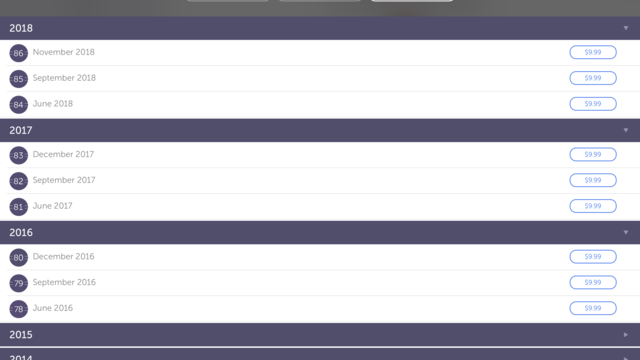

Since these topics are commonly tested on the bar exam, we figured this story would be a perfect way to review them (and remember them!) as you continue your bar exam prep.

The Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment requires that confessions be voluntary; otherwise, they are inadmissible. Whether a confession is voluntary is determined by looking at the totality of circumstances under which the confession was given.

Recall, too, that the Bill of Rights, including the Fifth Amendment's Due Process guarantees, is made applicable to state and local government action through the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. Thus, if the local and state officials who interrogated Dassey coerced his confession, that confession is inadmissible and cannot be used as a basis to sustain a criminal conviction against him.

So, what exactly happened to Dassey?

On February 27, 2006, state and county investigators interviewed Dassey. At this time, Dassey was:

- 16 years old,

- with an IQ that had been assessed as being in the "low average to borderline range,"

- had "difficulty understanding some aspects of language and expressing himself verbally,"

- had trouble "understanding and using nonverbal cues, facial expressions, eye contact, body language, [and] tone of voice," and

- received special education services at his high school.

The investigators initially questioned Dassey for an hour, alone, in a conference room at his high school. They then contacted the prosecuting attorney, who reviewed the audio recording of the first interview and asked for a better record.

The investigators contacted Dassey's mother, Barb Janda, who went to the high school and then traveled with her son and the investigators to a local police station equipped with video recording equipment. According to Ms. Janda, the investigators discouraged her from joining Dassey for this second interview. Thus, Dassey was interrogated again, alone, for almost an hour. During this interview, Dassey told the investigators that he had been present with Avery the night of the crime.

Believing that Dassey knew more, the investigators obtained Ms. Janda's permission to speak to Dassey once more, on March 1, 2006. According to Ms. Janda, the investigators never asked her if she wanted to be present for this interview. Instead, the investigators picked Dassey up from school the morning of March 1 and read him his Miranda rights.

The Fifth Amendment requires that the Miranda warnings be given to anyone in police custody before police interrogation.

Dassey agreed to speak with them. This March 1 interview was the fourth time in 48 hours that the police had questioned Dassey. The interview began shortly after 11 a.m. at the Manitowoc County Sheriff's Department. The interview was video and audio recorded. No adult was present on Dassey's behalf.

For the next three hours, the investigators prompted Dassey to tell them a sordid tale of rape and murder, all the while assuring him that they already knew "what happened" and telling him that they were in his corner.

After "confessing" to this crime, Dassey told the investigators he had a project due in sixth period and wanted to be back at school by 1:30pm. Additionally, when the "interview" finally concluded, the investigators told Dassey they would be arresting him. He asked "Does my mom know?" and whether he would be in jail for just one day. He clearly had no understanding of the implications of what had just happened to him.

(For a detailed blow-by-blow account of the March 1 interrogation, see pages 5-20 of the district court order. For an account of the unforgivable misconduct perpetrated by Dassey's pre-trial defense lawyer Len Kachinsky, see pages 21-35 and Episode 4 ("Indefensible") and consider the violations of Professional Responsibility; file under "How Not to Practice Law.")

Considering these circumstances in their totality, Judge William E. Duffin held that Dassey's confession was involuntary, because:

- The investigators repeatedly told Dassey that they already knew what had happened on the night of the crime, and

- The investigators repeatedly assured Dassey he had nothing to worry about. These false promises, coupled with the investigators' leading questions and other pressure tactics, plus

- Dassey's age (16), and

- intellectual deficits (low IQ), and

- the absence of a supportive adult (a parent or competent defense lawyer), rendered Dassey's "confession" coerced and unconstitutional.

What happened to Dassey is a case study in coerced confessions and an extreme example of a miscarriage of justice. We hope this post will help you remember the key rules related to a criminal defendant's most precious constitutional rights.