- Summary

- Transcript

Meeting Purpose

To provide an open forum for LSAT prep students to ask questions and review challenging logical reasoning problems.

Key Takeaways

- Mathematical reasoning questions often test logical thinking about numbers rather than actual calculations

- Diagramming can be helpful for complex sufficient/necessary conditional logic, but isn't always necessary

- Must Be True questions require carefully connecting ideas in the passage, sometimes in non-obvious ways

- Anticipating answers can be useful, but being too rigid with expectations can lead to missing correct choices

Topics

Mathematical Reasoning Question Analysis

- Examined a fuel efficiency question (PT5, S2, Q15) involving break-even points

- Demonstrated approaches like graphing and using concrete examples to understand the logic

- Key insight: Falling fuel prices make the less fuel-efficient option relatively more attractive, counter to intuition

Must Be True Question Strategies

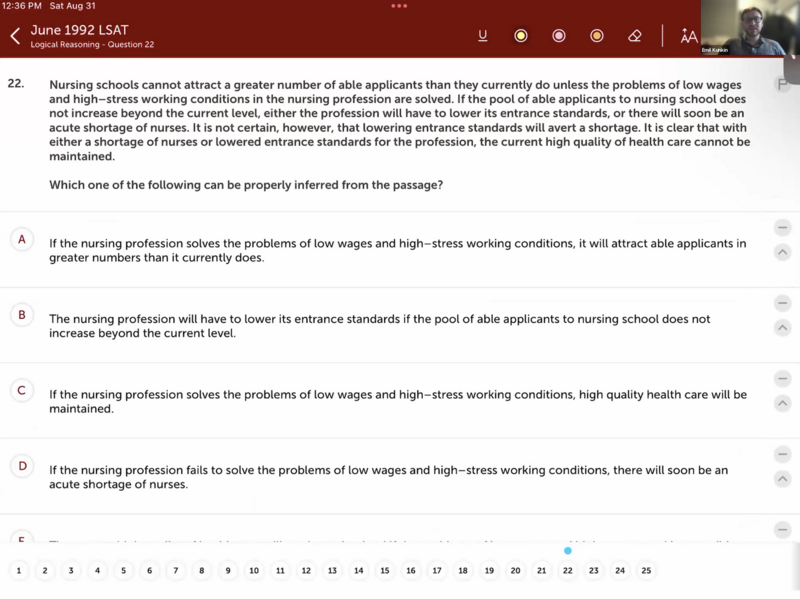

- Analyzed two Must Be True questions (PT5, S2, Q22 and Q12)

- Q22: Demonstrated value of diagramming for complex conditional logic chains

- Q12: Showed how correct answer may express key idea indirectly (population increase)

- Discussed balancing anticipation with openness to unexpected phrasings of correct answers

Diagramming Techniques

- Useful for visualizing complex conditional logic chains

- Can help anticipate answer structure, especially for long chains

- Not always necessary - judgment required based on question complexity

Next Steps

- Practice identifying when diagramming will be truly helpful vs. when to rely on careful reading

- Work on recognizing indirect expressions of key ideas in Must Be True questions

- Continue to develop anticipation skills while remaining open to unexpected phrasings

This is a hundred percent your guys time So if you would like, if you guys have any questions, absolutely feel free to pop them in chat, come off mute, et cetera.

If not, I definitely always have a few topics I'd love to ram out, but this is your time. So any questions you guys have, go ahead.

Sorry about that. And if not, I would love to take a look at this question, I think it really is a good example of what mathematical reasoning looks like on the field, where it's not asking to do actual math, but I do think that it's flexing math.

the muscle that thinking about numbers in a logical sense muscle. So if we don't have any questions right now, we can definitely take a look at question number 15 of prep test five, section two, and in that case, unless we have any questions coming in, absolutely feel free to ask anything of course, always feel free to interrupt.

But if not, let's take a minute or so just to read through what the passage is talking about, and think about the argument.

You So hopefully we have had a chance to read through this and if you're feeling a bit confused, you would not be alone.

This is a very tough question, it's a very tough question for a reason. we have two options here. We have the normal option and the high efficiency option.

So it makes enough sense. One thing I'd love to do when you have real world scenarios is try to put yourself in that scenario.

So I have two options, it doesn't matter what they are, it's a piece of equipment because you have operating costs and have product cost, sports car makes perfect sense.

I actually do like this example, there are much more high level theoretical examples they could have gone with here.

So I'm happy this is actually like a real world thing in the thinking of. And we are told that the high efficiency one is more expensive upfront.

Yeah, that makes perfect sense. So if you want the energy efficient, the fuel efficient option, if you're spending more up

But, it's cheaper to operate because it takes, you know, we can assume it takes up fewer gallons of fuel per mile drive.

So, we're currently told that the breakeven point is 60,000 miles driven. So, in other words, that's saying that if you drive that car, you were in 60,000 miles, the amount you save in fuel is not going to make up for the difference in preference.

If you drive more than that, it will. And there's a couple ways to think about this. I am personally a big fan of drawing, just drawing it out, if that's something that you like.

And there's a couple different things we could draw out here. So, we could think about this in terms of, well, like a little graph.

And I think we're probably all familiar enough with graphs like from algebra, one, cetera. So. where the x axis is miles driven and the y axis is overall a total cost.

So we're gonna say that let's go to green for a minute. Green's green is not too green. Let's do orange and see orange.

So one option is more expensive but it costs less per mile driven. So let's say that's what it looks like and that makes enough sense because for every mile driven you're using less fuel this is the high efficiency orange is the high efficiency and then we have another option let's make this option light blue and that one costs less upfront so it starts down here.

But for every mile driven, it costs more to rot it. So in other words, that's what it looks like.

And that break-even point where they meet is 60K. Cool. That makes sense. That makes enough sense to me. But then, what do we have in If fuel prices fell, the break-even point would go down.

In other words, it's saying that if the amount it costs to run for each of both of these options goes down, that break-even point is going to shift to the left.

So, excuse me, what would it look like if they both go down? Well, just as a gut check, it probably is going to look something like...

In other words, they both get a ladder, both of, because again, for every mile, that's the variable cost per mile going up.

If that cost goes down, if the cost of fuel goes down, that means that a slope that previously looked like this is going to look like that.

It's going to decline. going to become a less sharp. But we see that as both of these become less sharp, then, well, that break-even point, I was actually further to the right.

It's gone up. It hasn't gone down. So that was one way we could think about this by drawing little charts.

I don't know if that's something that appeals to you guys, but don't worry, there is more than one way.

So I think one other option then might be to look at an example. I mean, we're told the break-even point is 60,000.

I'm going to use simpler numbers here. I'm going to use round, simple, boring numbers. So, let's take a look then at our two options.

So we have option one, which is option one, which is high efficiency, and option two, which is a regular.

And what I'm going to do here, I'm really just going to assign costs that I have made up. So let's see, we have the purchase price, let's say that the purchase price for, so, up front cost, purchase price, whatever it is, the high efficiency one is more expensive.

Let's say that that costs $20k. And the regular, let's say that only costs $10k. Okay, that makes sense. And we need it to be the case that it's cheaper to run the high efficiency.

So let's just imagine like gallons per month. Okay, I find the miles per gallon is probably actually the easier way to put it.

So. Is it we're just familiar with that? The high efficiency one gets 20 miles per gallon Whereas the regular oh actually now let's you know, let's make this even sharper.

The high efficiency gets 40 miles per gallon The regular one gets 10 miles per gallon So for any given I'm now driven.

Oh, sorry. Let's yeah, maybe no more work work on that one there for any Giving miles the total cost That's equal to purchase price Plus Miles per gallon Time yeah times miles Yeah, I didn't do us enough space for this sorry, so Do the summer where I actually go home of space You

So the purchase price plus the variable cost and that's basically probably better way to put this, actually just the gallons used times the cost per gallon.

And gallons used is a function of how many miles are driven. So what we're going to do here then, if we wanted to go through the math, I don't think we actually really need to do that here, what we really want to do is just look at, okay, what happens if that cost goes...

down. In both cases, that cost going down will make it cheaper to operate the car. But look at how many, how much, which one will this help?

Is that going to help the high efficiency one or the low efficiency one more? Which one will that make look better?

And that's actually going to help the option that is, excuse me, that's going to help the option that is cheaper to drive.

In other words, that's going to move that break-even point further to the right. It's going to to drive more miles for it to make sense to take the car that it costs more up front.

And that's because if we look at what total costs are actually a function of it, get the cost. per gallon goes down, that means total cost is going to go down, total cost.

I mean, this part of the equation is going to go down while the purchase price doesn't change. If the variable cost go down, that favors the thing, where variable costs were a greater portion of the total cost, and for the non-high efficiency one, that is what was happening.

And so in the answer choices, we're going to look for an answer that does the same thing. I want to pause for minute because this is just my example of how I like to go through a problem like this that has some mathematical reasoning.

But again, this is an open form 100% in your guys' time, so I'm going to pause for, excuse me, going to pause for minute or two because again, this is your time.

Any question, any topic, anything you guys want to talk about, happy to look at any question, any high-level, low-level jutter-up?

Actually, I, I do, um, let me pull it up, um, and while you pull it up, Moira, yes, the way you're thinking about it is way more sustainable.

We could go on and I'll, uh, I'll find it cool, and yeah, this is just, I'm just quickly to hide.

And this is something that I think intuitively makes a lot of sense and this is something you don't actually need to go into all this graphs and stuff if you don't want to.

That's something that intuitively is able to make sense to you. In other words, when you have a high fixed purchase price and then an operating cost, if that operating cost goes up, you're more willing to invest more money up front to save costs in the back end.

And this is something we see across, across industries. This isn't just about fuel efficiency, but yeah. Like, if gas prices are $5 a gallon, $5 a gallon, you want to buy a more fuel-efficient car.

If they're at $1 gallon, you probably don't really care. mean, I'll do the precise environmental concerns on the side.

But I think one example where we probably see this a lot, and you probably see this in the news of Fairmount, is about labor costs and automation.

There's a lot of debate. mean, the academic literature seems to actually argue against this, but at least in theory, the idea is that if wages go way up, that makes automation more attractive, because even if it costs $100,000 to buy the robot, if it's going to cost a lot of money to hire workers as well, that makes the purchase price more, the high upfront purchase price more attractive.

Because if wages go up, you want to save labor on the back end. You want to save labor costs on the back end.

And yeah, Joseph. So, if you're spending less money, then you're you're then then Yes, you do have the right, believe.

I'm a big fan though of trying to make this make more sense to you, however that looks. And if we were to replace this with engines, and if we were to place the special engines in cars in with something about labor and automation, that's something to pay personally.

I understand better. So I'm a few more comfortable that thinking about this question is one of, okay, you have two options.

You can either hire more workers, or you can hire, you can buy an automation solution that will solve something.

But when we just fall, okay, if we just fall, that makes workers more attractive, not automation. So you don't want the big upfront cost.

So that means that the high efficiency is actually less attractive in this example, which means that the break-even point is actually higher when gas prices fall or it will make it fall.

you. Yeah, if you guys are ready, go ahead, Joe. Sorry.

You can keep going. I'm still kind of, well, let's see, I'm still kind of looking for it, but. Yeah, you know, I'll come back to you and when, when, when I can find, I have a specific question.

I shouldn't have written it down, but once I find it in my notes, I'll.

Cool. Sounds good. In that case, if you guys want to take a look at the answer to this real quick here, I think that that will help us to understand that.

That's think that what we've done here will make these answer choices way easier and way less horrible because this is, again, this is a very difficult question for a good reason.

But let's take a look because the right answer is going to be the exact same thing. where it's confusing the idea that, oh, wait, it wages fall, that makes it easier to hire workers.

In other words, if something gets cheaper, we want to do more of that, the right answer here is going to confuse that and say that, oh, something got cheaper, so we want to do less of that.

And that's exactly what I was trying to show, maybe didn't do it as efficiently as possible, and it's like total cost thing.

In this total cost equation, we have two halves of it. You have the purchase price and the variable price.

If the variable, and one of our two options has a higher purchase price, one of them has a higher running cost.

If the running cost goes down, that favors the one with a higher running cost. If the running cost goes up, that favors the one with the higher purchase price, the lower cost to run.

The right answer is going to confuse that. So let's look at the answer choices. And A just seems like it's kind of out of life that you'll hear.

So, this, we don't have the idea of two possible choices here. I also think that A is just correct, that, yeah, that the actual real rate of interest is interest minus inflation.

So if inflation falls, then the true rate can not be changed if the actual rate of interest falls as well, and yeah, that makes sense.

I think this is factually accurate, like I think this is a valid argument, but more than that, we don't have this element of, we have two options, A and B, one is more expensive but cheaper to run, one is cheaper but more expensive to run.

We really need that structure, so I don't want to even think more about A, it doesn't matter that it's a valid argument, it doesn't matter because it's just not what was in the passage.

And B, we do have this, so we have two freezers, and it looks like the is do have an element of one being cheaper.

Well, so not exactly, but it's close enough. We have the idea that one of them is more expensive to run than the other, but the one that's more expensive has some other benefit.

So that benefit could have been it was cheaper to buy, but that benefit also could be that it generates more profit.

So, I mean, those are really the same thing. We're saying that one of them has a benefit in terms of being cheaper to run, the other has a benefit in terms of revenue generated.

Same revenue generated or gone costs, they're the same thing. So, we don't need to worry about that too much.

I do like that at first it does have the structure that we were looking for, but let's make sure that it is making a flaw.

So, let's see if it's actually a bad argument. So, we're told that polar allows more profit. polar, is the one that is more profitable, but it's more expensive to run.

So in other words, it gives the bigger benefit, but it has the bigger cost. So if electricity rates fall, okay, so remember we have two options here.

polar and arctic. polar, it's expensive to run, for arctic, it's cheap to run. If the cost to run it falls, which one does that favor?

That favor is the one that's expensive to run, I think. If instead of, let's say, if electricity last year would have cost 20,000 for polar and 10,000 for arctic, but this year, electricity rates have halved.

So that means polar now only costs 10, but arctic is It's only $5,000 cheaper. And since polar is better for another reason, if electricity rates fall, that actually helps polar.

That helps the more expensive one, the one that was more expensive to run, which is what the argument actually sets.

So I think that B is correct in the sense that the argument is valid, but it's wrong in the sense that it's not making the same mistake the passage made.

The passage said that if the variable costs fall, that favors the one with a lower variable cost. Here it's saying that if the variable costs fall, that favors the one with a higher variable cost, which is actually correct.

So I think B is a good argument, which is why it's wrong. So B looked really promising. It had the right structure, but in the conclusion, it said the opposite of what we're looking for.

Have I made sense how I say that?

it has the same structure initially I picked E, because I didn't see E, but now I'm leaning more towards G right now, but B seems like a valid argument, right?

It's not really flawed. Yeah, that's the issue with it. It's I'm not going to go and say that this is a hundred percent valid.

There could be either could be other flaws I'm not really looking for here, but yeah, it's that it is that it does not have the same flaws, the argument because that yeah, it's valid enough for us.

that is always something I want to be on the lookout for on parallel reasoning, sorry parallel flaws, but arguments valid.

doesn't Yeah, B looks very promising. had the right amount of things. It had the right structure of the benefits and drawbacks of the two elements, but then it actually was right in the end.

Cool. So in that case, I think that we can probably look on at C. again, right after that, I like C.

It does seem like we more or less have that structure that we were looking for. In other words, we have two options.

We have an option and a half. Well, I guess we actually do have two options. Roadmaker or not Roadmaker, unless I'm reading this not carefully at all.

So we're told that, oh no, the competing model, wow, I'm not reading that carefully enough, which by the way is how you get questions wrong if you don't really care for it out.

We have the Roadmaker. we have the other option. The roadmaker is cheaper on the back end. It saves you labor costs.

Same thing as saving gasoline. I mean, that's for the purposes of this question. Very much not what I mean to say, but it's saving us labor costs.

It's saving us the cost of operating the machine, even though it's more expensive to buy it up front. So, C12s then, when wages are low, one of them is favored.

If wages are low, would I rather the thing that is more expensive to buy the cheaper to operate? So, in other words, wages are a smaller proportion of the total cost, or would I rather the thing where it's cheaper to buy a bit more expensive to operate?

other words, where wages are a high proportion of the total cost. And no, if wages fall, I want to be using more labor because it got cheaper.

So, I want the thing where labor is a higher proportion of the total cost. In other words, I want the competing model.

And that's the option of what C says. So yeah, Harry, Joe, I agree. I really like C. That seems like it is exactly what was happening in the passage.

We say we have the variable cost falling, but then we favor, we say that favors the thing with the lower variable cost when in reality there was the higher.

And yeah, I really like C. I would maybe still quickly read Knockout DNE, but having Redstein now, I really, really like it.

So with that, yes, because as far as like after you read the stimulus, and you know, you look at answer choice D, and you say, and you see, you know, in the conclusion, the words should, would that automatically knock that that out?

Like, we don't have any normative phrases. That's why I thought, he doesn't really look that good for that reason.

That's a really good question because normally I would say yes, but I think there could be, so I mean, the way it's used here, yes, I think it does knock it out.

Because I agree, the conclusion is not really normative. It's saying that if this happens, this option becomes more attractive.

That said, I could see them using the word should in a non-normative sense, really, like they could say, therefore it follows that if fuel prices fall, it should take fewer miles.

Now, I don't think they would do that because think it does mean something different, but in common speech, I think the words it would take and it should take could be used interchangeably there.

So I would say like 99% of the time, yeah, the word should is disqualifying, but I think that they could phrase it like if fuel prices fell, a business should favor the option, this option, because it is cheaper to them.

And that's really not saying anything different than the passage. Okay. As long as it's being used in a sense that's not beyond the logical force of the passage.

If that makes sense, because the passage is saying that if this happens, this is cheaper. So, I think it is, and I guess what I'm saying is slightly different from that.

It's different from saying that, therefore, the bridge even point is lower. That's not saying, therefore, we should do that, because there could be other factors.

Yeah. If they're using should as, that's doing an opinion, right?

But if they- Yeah, opinion.

Okay. if it is kind of like opinion driven, then, then, and if the stimulus isn't, then it should be kind of thrown out, right?

Yep. Okay. absolutely. So, yeah, I think a better way to say it is, if that should seems like it is making a suggestion, therefore, we should do actually this indeed.

By actually, yeah, having said that, I'm probably not going to read. I'm not going to read the first two sentences of D, because now that I see the back conclusion is so clearly normative Not reading it, but I don't care because the passage didn't tell us therefore It should be option A.

The passage says that oh if this happens that makes this more capable Completely different completely different logical course there.

So yeah, I agree. I would not get D in because it should Or more accurately I would not get D.

because of the should indicating that conclusion is normative Cool I'm looking at E Okay, so E I mean E kind of looks fine to me is that I think this is just a valid argument We do have few options, but we don't have difference in cost here.

We're talking with a difference in volatility And we're saying that, OK, people who want less volatility should choose the less volatile thing.

That seems like a valid argument to me. So I'm not going to pick E and going to safely with C.

Cool. Thank you guys for indulging me on this little rant about this one question. I came across a message word question yesterday, and I thought it was a really tough one question below that.

That said, this is still 100% of time. So any questions on any topic about anything whatsoever, happy to feel them.

Okay, cool. Yeah, so we can definitely look at some must features. And, you know, I bet there's definitely some must features in this section, which means that we don't really have to move too far.

Oh, yeah, here we go. It's 22. This looks like it's going to be eight stuff. Oh, yeah, I even remember this one.

actually, Mario, does this look familiar to you? Because I think this is one that's used in like the must be true packet, the module.

And if not, we can take a look at this one because I think this is a great question. And, of course, if you have specific must features, you want to look at let me know and we can look at those instead.

And this is a very tough must be true. So, let's take a look at this one and can look at a different one, hopefully a fresh one after this.

Let's take a full minute just to redo this passage because this is a So, my first question on this one is, do you guys think this is something that that would be helpful to diagram?

And this is just a gut field, would you want to diagram this, having that?

At first, my gut said that I didn't want to diagram it, however, after reading through it, might be to use the time in my opinion.

I'm really on the fence about this one, as we do have, I mean, we do have sufficient necessary. But, when we have a thing

amount of it, but there's nothing that's too insanely complex here. So, I, this is, I've said this before, but I think there's two real use cases for diagramming.

One is if you're not sure, but you think you understand it, that diagram can be helped to get it on the page and visualize it if you're a very visual learner.

The other one is when there's a lot of stuff there, it's taking it out of your head and putting it the page so you don't have to remember it.

So, you can go back to a diagram and not have to go back to your head. This is one where, since I'm on the fence and since, you know, we have the time, let's do it, I think I would, I'm not sure.

Yeah, I'm not sure if I would bother doing this on the past if I were seeing this for the first time, but it's one where it's such a borderline case that I think it could be helpful to the diagram.

So, did you scroll down to E real quick? Actually, it's just, I'm going to quickly, go to landscape, not landscape portrait.

I actually don't know which one's which. think this is portrait. think the sideways landscape, but never really thought about that for bothering to learn.

But yeah, I probably would want to diagram this just because there is so much here and we do have relationships.

But let's then look actually at how we want to diagram this. So the first statement, it is conditional and we're told that they're not going to get more applicants unless we solve the problems.

So in other words, and by the way, this is something that I really if there's one thing you guys take away from today, I want you to think that the word on less just means if not.

So that first sentence is really the saying that if we do not solve the problems, there will be an acute shortage.

So in other words, if not solve problems, then nursing shortage. that's bad. That doesn't seem good. And wait, actually, no, that's not exactly what I said.

Nursing school shortage, that is a critical difference. And that's the thing why when you're doing questions, when you're diagramming, I want you to be specific, because a nursing shortage and a shortage of applicants is not the same thing.

So what does this say? says not attract able applicants. So let me say schools attract applicants. Important difference there.

So I think that's important. And maybe we might want to take the counter positive here is like, it's useful to know.

if schools attract applicants, then it must have been that we solve the problems. We don't have to do that.

We can doesn't really matter too much. Next sentence. So if we do not get more applicants, and by the way, I'm absolutely different.

So It said something different, the greater number, able to attract a greater number of applicants versus the pool of applicants increasing, that's the same thing to me.

So in other words, I'm going to say that if we do, if we do not increase the numbers, so if not, so if we can't get more applicants, then one of two things will happen.

It will be that we'll have to lower standards or shortage, L S, or S H, and by the way, for orders, I just kind of want to like box it because we don't know which one it is, we know it's at least one, maybe it could be both, it doesn't really matter, here the org doesn't really matter for us because we're told that, okay, this next sentence actually we can kind of ignore it.

We're told that it's not guaranteed that lowering standards will even avert a shortage, might Like not doesn't matter because that less infant tells us that with either a shortage or lower standards The current high quality of care cannot be maintained.

So what it's saying is that either way based on this box High quality of care, that's not a C will not be maintained And this is tough There's a lot going on here, but We actually have a pretty big chain because we're told that If we can't solve the problems Oops, I should then Oops, sorry if we can't solve the problems Then we will not have enough applicants if we don't have enough applicants There will be one of two bad things And if it's one of two bad things the quality of care won't be maintained We can make this a big chain that tells me that if we don't solve the problems the high quality of care will not be maintained And if we look at

the answer choices. I think a lot of folks have already hit on this. That is exactly what we are saying.

And this is something that I think really does help us in diagram. This is a reason why diagramming had been helpful.

Because we were able to anticipate that right answer by making a big change. And we didn't know where it could have been.

They could have told us that if we don't get more able applicants, the high quality of care will not be maintained.

They could have started later in the chain and gone to the conclusion. doesn't really matter. The point is we had a big chain.

And it was much easier, at least easier to me. And it might even be helpful to just draw the chain.

So not SP means not get more applicants, which means too bad things, which means not high quality of care.

And that's our big chain. And the red answer is just going to be something on that big chain. Like, I would say 80% of the time on a bus feature, when you can make a big chain, the red answer will be either something that's on that big chain or it's on the counterpart of that big chain.

And so when you do have a lot of special necessary, I do think diagramming can be pretty useful. Just because you don't have to think through it, you can just visually see it if you're a visual learner.

So I do agree with when things get very, very difficult on these questions to diagram. However, with this one, I read it and I came up with an anticipation.

And I still, this was still hard. But like what I just, after reading it, what I thought was like, I actually wrote it down and I said, well, then the current high quality of healthcare can't be made.

maintained, the healthcare quality will decrease. That was actually my, that last part was my direct anticipation, healthcare quality has to decrease something.

So I didn't work out any drawings or any kind of a diagram on this one. Is that okay? Sometimes like if you have, yeah, if you, if you're really confident in your anticipation, don't doubt that, right?

Because I did that the other day on the test on a practice test they took. And I was kind of running out of time too.

So I went back and I switched an answer choice to the state with it because I got it. I would have gotten it right.

So, you know, if your anticipation, you feel like it's, it's very spot on. This seems like the perfect example of that and just saving as much time as you can.

Yeah, I don't have two minds about this and I would say that that's because if you have a clear anticipation, that's good, and if you find something that clearly matches that anticipation, that's great, but I also want you to always be willing to move away from anticipation if there's nothing that comes even close to that because it's very easy to get stuck with your articulation of an anticipation, and they may articulate a very similar idea in very different ways, which having a very narrow anticipation can make it harder to stay.

So I really like keeping my anticipation at at least like the thousand foot level, if that makes sense. So like for this one, I would probably say that oh yeah, so unless we

we solve the high stress-low wages problem, bad things will happen. That's probably how I would have approached this, rather than saying, oh, the quality of health is going to decline, because we don't know that it's going to decline.

They might solve the problems instead. But I do like keeping it at a relatively high level, just because I personally find that if I have it, if I say, oh, the right answer is A, B, E, which is an example, is x, y, z, whatever.

And it's really something very similar to that, but not phrased how I expected. I'm more likely to miss that for the time, because I was so laser focused on my anticipation.

So I think a lot of it depends on like, is that something that you feel yourself doing? Do you feel like I have you missed questions because it was, oh, I anticipated x, y, z, and really it was x, y, z alpha.

Or it was y, x, z. If that's a mistake, if that's a reason why you see yourself missing questions.

questions, then I probably would try to move away from having as firm anticipations, but if not, then still put their anticipations.

Am I making sense? So I say that?

Yes.

Cool. I'm going to, I guess, sort of address these questions in reverse order. So let's look quickly at C to see why it's not C, because C does, oh, yeah, C does give us the right ideas, but what's the relationship in that?

In E, it's saying that unless we say, again, unless this means if not, if we do not solve the problems, then high quality will not maintained.

So in other words, E is if not solve problems, then not high quality of care. And is that on our chain?

Yeah, I think it is. Because that really is just our big chain wrapped up. Let's look at C, then.

C says, if we solve the problems, high quality of care will be maintained. So C is if solve problems, then high quality.

Is that on our chain at all? That's what it is. It just negates without reversing. That's just not on the chain.

That is, I guess we call it a legal reversal, whatever. It just negates without reversing E. And since E is on the chain, we can pick E, but C is just not on the chain.

Like, there's just nothing in the passage that tells me that if we solve these problems, it's guaranteed that the high quality of care will be maintained.

It's totally possible that we solve all these problems. But, okay, a real world example. pandemic comes in and it really just, it's healthcare workers especially hard, a lot of healthcare workers are virtually killed and a lot leave the field because it was just so stressful.

And so the quality of care falls, even though we solve the problems. And that's something that's totally possible according to the passage.

The passage never tells us what will guarantee us to keep the high quality. It's telling us what will guarantee us to lose the high quality.

So more, oh, so you have a question. Sometimes you do diagram correctly but you don't correctly back to the answer choices.

And I think this actually gets a little bit to what I was talking about with Joe because I think there's definitely more than one reason this could happen.

But I think the two most common ways this would happen would be that you, I guess there's probably three things that I think could be happening here.

And let me know if any of these sounds like something that you've felt happen. One may be your diagramming where we don't really need to diagram.

That's not, excuse me, that's not something that is an issue with diagramming. That's an issue with remembering that the right answer is just something that we can prove from the passage.

It doesn't have to be something that is necessarily like in our diagram. But in terms of the actual two more common ways that I would expect what you're describing to happen, one might be what I was trying to do earlier that you have a good diagram and you really expect it to be, oh, well, the passage tells us it was if a then b, if b then c, I really think it's going to be if a and c.

But in reality, it gives us a slight, a slight tweak on that. Maybe it gives us the contrapositive of that.

So it might be that you're getting some tunnel vision. I don't know if that's something that it feels like is happening here, or it might be that the right answer is something that is using different words, that is using the same idea but expressing it different ways.

way. So maybe you were expecting if a then not b, or sorry, if not a then b, and it gives us b unless a, because again, unless just means if not.

So I think those are some of the more common ways for what you're describing to happen. Does it sound, do you have a good sense of, or specific, do you have specific examples of questions where this is happening, so let's look at that.

But if not, I definitely think that focusing on ideas expressed over the exact wording is something that I think a lot of people, wait, that's in a good way.

I want you to focus on the idea expressed over the exact wording, because I think failing to do that is a really good, really common way to diagram well and understand well, but to still miss the right answer, because it expressed the same idea or expressed the idea we were looking for, but just in a way we did not expect.

And I feel like that is actually pretty common on the I must be on must be curious. If you guys want, we can look at another recipe but true for anything else really.

Cool, so if not then, I'm very happy to look at maybe 12, which is another must be true. And let's take a second to read through it.

Oh, this is weird. Okay, so hopefully we've had bit of a chance to read through this. And looking at the passage, looking at what this is saying, interesting, we are told that the number of children who are obese is steadily increasing according to four major slarts.

That makes enough sense, but we also really want to dig in, and by the way, this is a question I don't think I have a diagram because we just don't add sufficient necessary whatsoever It means to be obese in this passage because it defines it It's defined as somebody who has a child who has more body fat than do 85% of North American children.

Yeah, agree with you because it's defining obese as the top 15% And if the top 15% has increased that just means the population increased and this is one where I think your anticipation is spot on and I would then probably just go into the answer choices and Excuse me.

I would probably go into the answer choices and I really would hunt for this one So yeah, like Joe I would be totally fine with your anticipation being spot on here Because there is one very clear thing we can take away from this But I would still let there be that like five percent doubt

back in my mind that I would let another answer choice that clearly is true, talk me into it being right, but I'm going and really hunting for the idea that the population is increasing.

And do we have an answer choice that seems like it gives us that idea? So looking at A, no, that just isn't expressing something even remotely like that idea, looking at B, that again, that doesn't tell me the population is increasing.

Look at C, that tells me population is probably increasing, and it tells me it is. Because if the number who are obese is increased, as in if the number of kids in the top 15% is increased, that also means the number of kids in the bottom 85% has also increased.

So C gets to that idea, and it's not really how I would have expected to be phrased, but it does get to that idea that population is increasing.

So I really like C, I... a still re-d and even going to be really, really skeptical of M, so D, we don't know that.

And again, that's not the idea that population is increasing. And again, looking at E, that is not supporting the idea that population is increasing.

But C does have to be true. C is just another way. It's an angle in, it's a backstory into saying that population is increasing, because if the non-obese children are increasing, that means that according to this path, they only have two categories, and they're both a percent of the population.

So if one category is increased, the other category must have increased as well, because population is increased.

So it's basically, I agree the way it's worried, didn't stand out to me. Like I said, A is out, B is out.

And I think I quickly went over C and was like, oh, that doesn't sound right. didn't get to D and E.

yet. Like, what, okay, so D is saying over the past 15 years, the number of children who are underweight has to climb that wouldn't, that wouldn't really make sense.

And more importantly for D, do we know what anything about children who are underweight in passage?

no, no, not at all. So that's kind of out of scope. And the growing older, that's kind of out of scope too, right?

mean, for me.

Do we know anything about that in the passage?

No.

passage gives us any idea.

No. And by the way, that's what wrong answers and most features often feel like. It's just like, I have no idea.

What? And right answers often are something that you do have to work for to tie it back to this picture.

And that's what we have with C, right? Like, C isn't saying that population has increased directly, but C is true, then population must have increased, because if the bottom 85% has increased, that means population's a whole more must have increased.

Right. let's just go ahead. There's more, there's more babies being born over the past 15 years and the number of those babies that aren't obese increased, well, that's meaning that there is some kind of seed doesn't just come out and say, oh, the population has increased, but you have to read around the lines a little bit for C, right, like, it's what's implied by C is that.

population has increased.

No, absolutely. And that is one of the reasons and more I wonder if this is something that I think this gets that second category I was talking about earlier of questions where the right answer expresses an idea that we could have got I mean not a diagram but like expresses an idea that we hit earlier but it expresses it in a weird way and that's what C is doing because it's not explicitly telling us populations increased but if population has increased then C must be true and vice versa if C is true population must have increased.

So it's not coming out and saying population increased but if we think through the implications of C then the population must have increased and if we think through okay let's imagine that 15 years ago there were 1 million kids which meant that there were 850,000 not obese kids and there were

150,000 obese kids. If we're told that today there's 300,000 obese kids, well that means that the population of overall kids must be 2 million and the population of not obese kids must be 1.7 million.

So, oh yeah, I guess based on the passage, it must be, and based on that little example, it must be true that the number of not obese kids has increased.

Because population has increased. And I do think that, excuse me, I do think that that's totally normal and very, I mean, happens to 100% everyone, I'm pretty sure.

Right answers will often not jump out as right, we have, but they get to the same idea, then it's up to us to draw the dots.

It's up to us to connect those dots to show why it's right. Any other questions? And if not, thank you guys for joining and enjoy the rest of your long weekend.

I'm going to make sure that I didn't miss any questions in the direct chat because I realized that I didn't miss a question, I'm sorry, oh I did shoot, I'm sorry about that.

Okay, I'm sorry, I didn't miss one question. First and second spot. anyhow, thank you guys for joining and enjoy the weekend.