- Summary

- Transcript

Meeting Purpose

Open Q&A session for intermediate LSAT students, focusing on must-be-true questions and quantifiers.

Key Takeaways

- Must-be-true questions become more complex at higher difficulty levels by combining multiple techniques like multiple valid outcomes, superfluous statements, and tricky wording

- Quantifiers are heavily tested in must-be-true and parallel reasoning questions, often at high difficulty levels

- For complex argument structure questions, knowing LSAT-specific vocabulary and breaking down abstract answers into chunks is key

- With parallel reasoning, quickly identifying concept-based vs. conditional logic questions can help with time management

Topics

Must-Be-True Question Strategies

- Multiple valid outcomes often appear in 2-3 star questions

- 4-5 star questions combine multiple techniques: Multiple outcomes Superfluous statements Contradictory premises requiring contrapositives Tricky wording in answer choices

- Diagramming conclusions before looking at answer choices is crucial for higher difficulty

- Be aware of quantifiers, especially in 5-star questions

Quantifiers in Must-Be-True Questions

- Focus on minimum overlap between categories when diagramming

- Look for guaranteed overlap between categories in answer choices

- Venn diagram approach can be helpful for visualizing relationships

Argument Structure Questions

- Higher difficulty questions use more abstract language

- Key strategies: Learn LSAT-specific vocabulary (e.g. generalization, hypothesis) Break down complex answers into smaller chunks Identify each component before evaluating if it matches the argument

Parallel Reasoning Question Tips

- Distinguish between conditional logic and concept-based questions

- Concept-based tend to be faster to solve

- ~25% of regular and ~50% of flawed parallel reasoning are concept-based

Next Steps

- Practice diagramming complex must-be-true questions with multiple statements

- Review LSAT-specific vocabulary for argument structure questions

- Work on quickly identifying concept-based vs. conditional logic parallel reasoning questions

- Study Venn diagram approach for quantifier questions

Okay. Moira.

Hi.

How are you today?

How are you?

Surviving. Yeah. Relaxing stuff to morning. I got to do invoicing and stuff this afternoon. So I, then I go roller skating tonight.

So I can't about that. About you. Yeah.

I'm doing pretty good.

Hey. Hey. Very. Thank you much. You Well, today is an open Q&A, so if anybody wants to start hearing questions or putting them in chat or anything, you're more than welcome to go.

Give about one more minute. Okay, let's get going. So I hear about must be true questions first. So we can kind of dive into those.

I think most of y'all have seen this document before, my conditional logic primer. So I've had a fair bit about must be true is here.

Basics go without saying, I know all of y'all have been studying for a while so you understand this, the general calculus of what it must be true questions looking for.

But if we're like kind of looking at things at the intermediate level, I did a big survey at one point of what I just call like must be true difficult to enhance.

Right, so just kind of like what do they do to make a must be true go from. one to a two to a three to a four and to a five and what I found was it's usually a combination of multiple of these things right here so at like the lowest level one of the things you start seeing in two and threes a lot is where there are multiple valid outcomes right so if we think about like a set of premises like a to b b to c c to d that actually gives us three separate inferences that must be true right a to c must be true a to d must be true and b to d must be true so part of that intermediate level is recognizing that there are multiple theoretically correct answers right it's just that the test makers are only going to put one of these three as an answer choice and they'll admit the other two entirely so

That's like, I would say, the first big bump that they try to push through with intermediate questions. And I can show you, like, this is probably the most extreme example I've seen them do.

It's from PT61, Section 2, Question 10, right? And if you look at this, you can see this entire sequence here follows each other, run to PH, PH, Plankton, and so on and so on, which actually gives 15 separate must-be-true inferences.

And, of course, they chose the absolute smallest inference as the correct answer, right? Not the biggest one, run off to few fish, nope, they chose the very smallest one.

So this is a big go-to for them, push things from 2 to 3 and then from 3 to 4.

Or they use this a lot. I'm sure all of you have seen this one, plenty, right, but just superfluous.

statements, right? You can imagine a prompt where two of the sentences don't really matter at all, right? You're really only using the first sentence and the fourth sentence and the other two are just there to create distractions, right?

So I always tell the students, I kind of urge them to just look for overlap, right? Like don't assume that everything you're given and it must be true has to be used.

Be okay with it not being used, right? You can feel comfortable with that because it's something they're intentionally doing.

See when, like, opposing premises, right? A to B, C to not B, right? This is really just demanding that you take a contrapositive, right?

Because then it becomes A to B, B to not C, therefore, A to not C. So what I'll say is with must be trues, once you get to like the four star level, they're going to start combining multiple of these things together, right?

So you might have like multiple must-be-true outcomes and a superfluous statement and a contradictory premise, right? So the question kind of demands that you take the contrast positive, you recognize that something isn't useful, and you'll be aware that there are like four potentially correct answers.

Right. The last thing I always say is that every conditional logic question is, oh, actually two second the last thing I'll say, quantifiers must-be-true questions are where they really roll out the truly difficult quantifier questions.

When I think of like a five-star quantifier question, I immediately think of a must-be-true question. So be very aware that this is the area that they test quantifiers the most and at the highest difficult.

Right? You'll see quantifiers use the fair bit parallel, but you see. that makes it easier because you're just matching the quantifiers, right?

You're paralleling them. You don't actually have to figure out how they all fit together. So I would say like a good third of the five star must be true questions or five stars because they lean deeply into quantifiers.

So that'll be a big difference too between the intermediate and advanced level. Yeah. And then the last thing I was going to say is conditional logic questions can always just be testing translation skills.

Very specifically, this one, right? Translating back from a diagram into a sentence, i.e. the end term choice. On the high level must be true just like the high levels of ambitious assumptions.

They're going to start playing with the wording of the answer choice such that it represents the right idea but it's never how you would have naturally phrased it, right?

And so just be very conscious that on four and five star questions, it's especially important to have a diagrammed answer, walking into the answer choices, because without that diagrammed answer, without that concept that you know has to be the answer, they're going to do a really good job of misleading you based on the wording of the answer choices.

Like that's their goal there. Yeah. Sure. Let's an example of a four and a five star, give me one second, okay, let me get my iPad out.

That'll be, please, yes. Anybody who else who wants to go ahead and submit questions and stuff, you're more than welcome to, and we'll just get to them as we end the order there, submit it.

All right. Sorry, you're to to give me a second because it drives me nuts that the must be trues and most strongly supported are in the same but okay so I know this one it's kind of like a low in four star so I'm pretty good one okay good a couple of really good questions all right so I'm doing a must be true if I'm just doing this organically I'm gonna just kind of math line by line usually with a must be true and a sufficient assumption I always start by mapping a conclusion and working back

but obviously here there is no conclusion yet. So, let's see. If I am right before to start, is this a practice of 1.82 logic reasoning to question up?

Thank you question 26. Thanks, just a reference later. No worries. Okay. So, a person is morally responsible for an action of only if that action is performed freely.

So, if I am morally responsible, then the action must have been performed freely, right? I'm just playing off this only if here.

An action is free, only if, so if it's performed freely, then there must be an alternative action that is genuinely open.

So, I'm just going to put geo, but an alternative action is genuinely Let me open, only if performing that alternative action is not morally raw.

OK, so this one actually ended up mapping pretty cleanly, right? I can just see my clear structure and my pullover.

So I basically got the answer that if I'm morally responsible for something, then there must have been an alternative action that was open, as in it wouldn't have been more morally wrong to perform that action.

OK, so this is really a question that's about translating this back into organic language, right? Very clean, diagram, very easy to add up, but actually figuring out how this should be worded is weird.

So I'm just going to go back again. If I am, if a person is morally responsible for an action, then there must have been an alternative action that would not have been morally wrong to perform.

I think that is the way to fit it. Okay. But I also have to remember this is a must be true.

And it has three phrases. So, M R to go, right, is also something that has to be true. And P F.

To not M W is also an independent thing that must be true. Right. So what you think about it is any like thing that you could add together.

Any set of two or more statements that can be added up. Are there own. It must be true and for us.

OK, sorry, I just wanted to. So just to make sure, because it's kind of like a light bulb, it just went off.

So basically, what you want to have multiple different outcomes that could possibly be what the answer choice to anticipate, because I see you doing like you have to multiple, you're doing multiple multiple, what's the multiple answer choices, and that's what you really want to do when you were before you died into the answer choice.

That's correct.

Yeah, if they have more than two statements that add together, then there's probably more than two conclusions here. Let me just, I can give you guys the rundown, right?

You can think of it as if I have A to B, B to C, then I only have one possible conclusion, right?

There is no additional combinations here. But once I add a third phrase, That means A to C, A to D, and B to D are all things that must be true.

If I add another phrase, then A to E, A to D, A to C, to D, all or not A to B, that one is already premised, these three must be true, B to E, and B to D is also must be true, and D to E is must be true.

So basically, we have four statements that means there are three plus two plus one outcomes. Six, when we have three statements, that means there are two plus one outcomes.

Three, and when we have two statements, there is only one outcome. And so, if we had five statements, that would mean there are four plus three plus three.

two plus one potential must be true inferences. So every time we add another statement on, we kind of do like an n minus one thing with the number of potential conclusions.

Sorry if that was over, explaining. But here we have three statements that connect together, which means we have three potential must be truly inferences.

And as I look at this one, right, let's just talk, an alternative action is not genuinely open unless that person would be responsible for would be morally responsible for performing the alternative action.

That's mixing up different pieces together, right? And more importantly, just doesn't match any of these three answers. B is out because it says most, and there was never a quantifier up here.

It was all if then statements. But C, C might represent this second answer. A person is morally responsible for an action.

If there is an alternative action open to that person. So this actually is not this. This would be if G, O, then MR.

So that is not the right reflection. If it would be morally wrong for somebody to perform an action, then that action is genuinely open to that person.

No, still not seeing that anywhere. Ah, an action is not free unless there is an alternative action that is morally wrong.

That one seems to fit, right? If I have an action that's performed freely, then there must have been an open alternative that was not really raw.

Right? That fits our last two statements when added together. So you can kind of see how they added a few different things together here, right?

They almost tempted us into one smaller answer, but it said if instead of only if, right? And we needed it to be only if.

And then still our biggest conclusion, right? The natural conclusion that includes all of the premises. Still not the right answer.

Instead, it's a different smaller conclusion. That is the right answer here. Okay. So. This is, I would say, like a high-free low-four, maybe a mid-four, right?

You can see that they're doing a lot of stuff. We have multiple statements. Our primary statement was to correct answer and translating these back and forth from regular English to diagram to English is particularly difficult because it's philosophy talk, and that usually ends up being like a word for Darville.

So, different sort of tactics they're adding together. Before we move on to a five-star, I just wanted to respond to a couple of things.

If it's parallel reasoning, sometimes skip them. Yeah, so I often tell people to think about reading time when they're deciding which questions to do first, right?

There's nobody holding a gun to your head when you're doing the test saying you have to do all of the questions in order.

And so, So, parallel reasoning questions, for example, are great ones to skip, especially if they're logic, because they're just going to be time consuming.

Even if it's a three star, it's going to take two minutes to do it, right, because you have to read a whole bunch of translations, match the structures, finally choose an answer.

So in general, when you run into questions that are incredibly wordy, especially if you run into them after the first 10 questions of this section, right?

You know those are going to be easier ones, but once you're beyond question 10, that could be a five star.

Just skip it and come back to it at the end. Better to use that two minutes on two other questions, rather than to dump all of that time into a parallel reasoning question.

Yeah? Okay, let's go check out a five star over here. I should have plenty down here. All right, this one looks successively wild, so let's check it out.

I also don't know if I've done this one recently. Okay, so if the infinite statements are true, which one of the following must be true?

By the way, this is 82-23. So, all highly successful entrepreneurs have, as their main desire, the wish to leave a mark.

Highly successful entrepreneurs are unique in that whenever they see a solution, they implement the idea. All other people see solutions to problems that are too interested in leisure time or job security to always have the motivation to implement their ideas.

Okay, so let's just start with, if I'm... I am a highly successful entrepreneur, then I want to leave a mark.

I'm seeing this unique concept, which is basically drawing a double arrow, right? So if I'm a highly successful entrepreneur, and only if I'm a highly successful entrepreneur, then I implement solutions.

All other people, so we can treat that as being if I am not a highly successful entrepreneur. If I am not a highly successful entrepreneur, I see solutions, but I'm too interested in job security to always have motivation.

So I'm just going to go ahead and do not motivation. So this feels like a way weird one, because to some degree it's like, okay, how do I connect these?

But the number one rule of contrapositive of diagram manipulation is that whenever you see something on the same side as itself, but once positive and once negative, you should do a contrapositive, Okay, so basically, if I am always motivated to implement the solutions to ideas that I see, for the problems that I see, that I must be a highly successful entrepreneur.

Which means I must want to make mark on the world or and also I always implement my ideas. Okay, that is the only connection I'm potentially seeing here, right?

Is taking that contra positive and then drawing a line to these two. Okay, so let's see. Interesting. So let's look at A.

Most people do not want to leave a mark on the world. So I guess we can say most people because we could maybe assume that highly successful entrepreneurs are less than half of the population.

But did they actually say that specifically? Anywhere, right, like, this is one of those things about conditional logic is even if it's a completely natural and reasonable belief to impute, for example, less than half of the world's population are highly successful entrepreneurs.

That's a pretty easy thing to assume, but they didn't say it, right? They didn't say it here, right? So I just don't think we can say that most people don't want to leave a mark on the world because it would reduce their leisure time or job security, right?

Also implies this once, whereas this is just saying that people are interested. It never says that those people don't want to leave a mark in the world.

It just kind of implies that they're not trying hard enough to actually achieve that. All people who invariably implement their solutions to problems have at least some interest.

No, that's drawing connection between two things that seem to definitely not. connected, right? If you are trying to invariably implement, then that means you're highly successful entrepreneur.

The main desire of all people who implement solutions whenever they want to, whenever they detect them, is to leave a mark on the world and ooh, sneaky, sneaky.

This arrow flows both ways, right? I said that earlier, that word unique, made this into an if and only if.

So, since this error, this arrow flows both ways, I think we could also draw the conclusion that if you want to implement everything you see, or if you are always trying to implement solutions, then that means you want to leave a mark on the world, right?

You guys can see that. It's a double-sided arrow, which means I can flip either side to be the same.

or the necessary. So that's interesting and I'm going to hold on to C. Generally, high success, highly successful entrepreneurs interest in leisure time or job security or not strong enough to have a so we're in conditional logic.

This is all if then statements other than the two always have the motivation, but at least the parts we have for highly successful entrepreneur are clear if that.

So saying something like generally is almost inherently wrong here, right? Because this is just if you are this, then you are this.

And finally, all people whose main desire to implement their solutions leave a mark on the above tempting very tempting.

But let's think about the difference between desire to leave a mark. versus actually leaving a mark, right? You see that little switch off of desire or wish and into reality, right?

This is saying that if your main desire is to implement solutions, then you do actually leave a mark. But again, this was just about desiring to leaving a mark, not about actually leaving one.

And so is out that we see the main desire of all people who implement solutions whenever they see them is to leave a mark on the world, right?

The desire is to leave a mark. Whereas here, the desire is to implement solutions, and you're actually leaving a mark.

So that's a very, I haven't done that one in a while. That was a fun and interesting five-star. You can see how they, like, that buried word unique and that

fact that it creates an if and only if relationship is what drives this correct answer here. Yeah. And even I missed it at first.

It's just as soon as I saw the answer that brought it up I was like oh that makes sense.

So the problem with D is that this is like an organic sort of take away. This is like a strongly supported takeaway, right?

We could reasonably infer based on this. It is supported based on this. The highly successful entrepreneurs care less about leisure time.

But that's not a conditional logic answer, right? conditional logic answer is math. These two things that I wrote are mathematically required.

If you agree with these three premises, you or require to agree with these two conclusions, there is no wiggle ground.

But D is not like that. D is organic, right? It is not a mathematical outcome of the equation. It's just an inference we could make.

Yeah. It's sort of like with those like the necessary assumption questions where one of the answers is a sufficient assumption rather than the necessary one, right?

Those little distinctions, they like to play with our heads, right? And that is something you'll see on basically all five-star must be truths.

One of the answers is almost certainly going to be like an organic inference that you could take away from the passage.

But it's not the must be true. It's just something that is strongly supported instead. Yeah, definitely like a tactic they like to use to muddy the waters.

Yeah. OK, so let's roll back. So I saw lawyer brought up some argument structure questions. So what I would definitely say about argument structure questions, especially once you're getting to that intermediate and advanced level of them, the answers to the questions become more and more abstract, right?

More and more removed from the actual wording of the argument. And much more just like a broad description of what's happening.

Methods and argument structure both love doing this, right? So if we like look at like a couple of beginner questions, we'll either have like, you can see how like these are like actually bringing up stuff from the passage, the educational, this is evidence that the educational system blah, blah, blah, then if you go all the way down to advanced lines.

You start getting like answer choices like this, it is a generalization of a particular instance which is cited by the argument in order to undermine the viewpoint that the argument is attacking.

No reference to the actual words anymore, pure abstract language, and that's what they, that's like their go-to to make these questions really, truly typical.

So, what I would say is, acing argument structure often comes into two things. One is knowing the vocabulary they like to use, right?

What is a generalization according to the LSAT, right? What is partial support versus complete support, right? What does it mean to say something is evidence?

What is a hypothesis, right? All of these words have a technical meaning on the LSAT. So, as long As as you learn that technical meaning, these questions become lot easier, as do methods and errors questions, because errors level 5s and 4s also love to get ultra abstract.

The second thing is how to cope with ultra abstract language, excuse me, I'm trying to plug this in, but I can't quite good at far enough.

So the answer to that is always answer chunky, right? So take a look at like an answer choice here of A, right?

That is a long, complex, wordy, abstract sort of state. So how do I break that down? Well first, I just ask myself, is it a generalization, right?

That's question one. So what's the generalization? It's kind of a broad rule, like a principle, right? It's not about a specific.

actual scenario, it's about something big, right, as sort of universal rule, right? two, what is the particular instance that this answer choice refers to, right?

What is that? Number three, what viewpoint is being undermined? And finally, number four, is this being used to attack that viewpoint?

A lot of students will skip straight to question number four, is it used to attack the viewpoint? But you can't answer that question unless you know what generalization, what instance, and what viewpoint is the answer choice even referencing.

Right? So, when you get to these highly abstract answers, make sure to slow down and individually identify each piece of the answer choice before asking, is this what's happening, right?

And then you can see like other ones on this answer choice a little bit better, but for instance, down here, what hypothesis is it a hypothesis at all?

Is it inconsistent with certain evidence? And does the argument that claim that because of that inconsistency, it must be rejected?

So again, not one step, not even two steps. This answer choice required three separate questions before I felt comfortable saying that I understand the answer choice and what it's trying to do, right?

So again, two real ways to master argument structure. Dr. two components to mastering it, my opinion, know the bulk half, and chunk down complex answers into bite-sized pieces.

Yeah. Does that help for my own? Right, go ahead. OK. Let's roll back up. Yeah. We also had that long text and long answers that take the time to quickly resolve them.

So look, I can give you some advice when it comes to parallel reasoning, for instance. So one thing I would say is that there are parallel reasoning questions are not one type question.

It is two similar but still very different types of questions. And I'm referring to this idea of a condition.

channel logic, parallel reasoning, which are usually very time-consuming and difficult, versus more concept-based questions, should Dr. parallel reasoning. Yeah, for instance, I look at this question, which the following is most similar, Watching video videos from the 1970s would give the viewer that the impression the music of time was dominated by synthesizer, pop, and punk rock, but this would be a misleading impression because music videos were a new art form at the time, they primarily attracted cutting into musicians.

I am not seeing a lot of double mentions, maybe music videos, but even then they just say music videos at the time or in a new art form.

Time- fairly attractive cutting it, this is an organic argument, right? This is a concept based argument, and the concept would be, if something is particularly new, right, it might not necessarily be indicative of the underlying facts, right?

So here, music videos, because they were so new, are not indicative of what music of the time was actually like, they're just indicative of what sort of bands would make music videos at that time, right?

So this is a concept based one, and it is much faster to do than the more classical conditional logic ones, right?

So a big part of acing parallel reasoning, or at least maximizing your points from parallel reasoning, is quickly identifying which answer, which cops are conditioned

logic and usually pushing those to the very end versus which prompts our concept based and therefore much easier faster to do.

Even if they're harder, at least you're not having to rewrite structure over and over again. So I'll say is something like 25% of regular parallel reasoning are concept based and something like 50% of flawed parallel reasoning are concept based.

So look for those concept based ones. What was the answer to the last one about music? Not this one.

was just kind of like looking at the parallel reasoning the way they're structured. not looking at the answers. I just kind of wanted to provide a little bit of like a background idea here.

But we can certainly do this one. So my thought is again... And my thought here is I'm looking for an instance where some new technology, right, is not necessarily indicative of the underlying field.

So, A is kind of interesting, right? Printing press literature can never be accurate because the surviving, worstly, ancient authors are those that were deemed by a copyist to be most likely of interest.

But this is more about using the new art form, right? It's not about like controlling the flow of information, it's just about using the art form.

So, I'm not sure A is quite a good fit, so I'll hold on to it. I look at B, this makes no sense in this context, so I don't like that one.

Now, see, see, I like, right, future generations of understanding of today's translation. be distorted, if they judge by works published in this particular format, just like music videos, because primarily publishers interested in computer games are using CDB.

oh, is this question. December 2011, we already transitioned to DVDs at that point, I'm pretty sure, pretty sure Blu-ray existed by that.

Anyways, despite the obvious age of this, I like C, right? It's getting at the idea that you can't study the overall field by looking at this one area, because the type of people that self-select into that area are different.

Um, song films or understandings few filmmakers realize that their films don't but disintegrate. Again, that's not about the self-selection of who's using a new type of art form, and then fashion trends, global TV programs.

like the most outrageous outfits. So again, this one feels a lot like A, it's about controlling the info, but it's not what we have up here.

It's not like music historians are controlling which videos we get to see. And that gives us C. Right. So in a concept-based one, you're really just finding the concept and giving a few words to it before matching it to other ones.

So someone brought up quantifiers, and it must be true context. That's a pretty good one. First, I'll just go ahead and point out, if you look at my teaching book for quantifiers.

What do you see? You see a lot of parallel reasoning, and it must be true, parallel reasoning, parallel reasoning.

Another must be true, parallel reasoning, parallel reasoning. Must be true, sufficient assumption, parallel reasoning, parallel reasoning. So you can see quantifiers are very, very heavily staffed in parallel reasoning, where they're actually kind of an easy asset.

Because all you have to really do is make sure that each sentence, like that the quantifiers are being repeated in the parallel reasoning.

So let's look at an actual must be true. That's a sufficient assumption. So I'll get a reminder, people, I do quantifiers the way I was taught, which is the event diagrams.

I find that the event diagrams diagrams are much better at understanding what's happening, right? So, I'll just start from the idea of every delegate to the convention as a party member.

And I want to emphasize to something to people. When we talk about quantifiers, at least this sort of adding them up and getting a solution, what we're really looking for is minimum overlap.

So, for instance, just take this statement. What percentage of party members are delegates? Does this sentence tell us anything about that?

It doesn't tell us precisely, but it does tell us what the minimum overlap, if every delegate to the convention is a party member, then that means at minimum some delegates or some

party members are delegates, right? But let's again look at that sentence. That sentence, every delegate to the convention is a party member, is equally susceptible to this construction, where there is a 100% overlap between the two, right?

This sentence is inherently ambiguous, with respect to PM's relationship towards D. We know D's relationship towards PM, but we don't know the inverse, which is why we only care about minimum overlap, right?

So this is the minimum overlap. If every delegate is a party member, then that means that these some party members are delegates.

So now I'm going to add on the second sentence, some delegates to the convention are government officials. I'm also going to make this a little larger, just so we can

You see this better if it doesn't keep redoing itself. Okay, so some of these delegates are government officials. Again, we could say that every delegate or every government official is a delegate.

But again, I don't know if that's true. So I'm gonna draw a little exterior piece. This is government officials and this is the overlap between delegate, party member and government official.

Now, each government official at the convention is a speaker. So I get to add another piece of overlap here.

But again, do I know that all speakers are government officials? I don't. So minimum overlap is that some speakers are government officials, but there might be a whole bigger category of speakers that are neither government officials.

Neither delegates nor party members, I don't know. All I know is that this is the minimum overlap between all of these categories.

And so, if I'm thinking about an answer choice to a must-be-true that uses quantifiers, this is exactly what I'm thinking of.

This is where the must-be-true must lie in the overlap. So, I'm just looking for some sort of overlap between delegate plus speaker plus government official plus party member, right?

Some of these people are all of these things. So, let's see, every party member to the convention is a delegate to the convention.

Possible? Right? that first circle I drew over here, right? Right? This is possible, but it is not a must-be-true, right?

The minimum overlap is what must-be-true. So, A is out, at least. some speakers at the convention are neither delegates nor party members.

Again, I can't know that, right? It is possible, but it's certainly not required. At least some speakers at the convention are delegates to the convention.

Yes, there is some people that overlap between being delegates and being speakers. The delegates, some of the delegates are government officials and some of those government officials are speakers, there must be this overlap.

D all speakers to the convention are government officials. Again, possible, but I couldn't possibly know that based on what I was given.

And the government official at the convention is a party member. Again, possible, but I couldn't possibly know that for certain.

And there we go. So that is my thought process. At the end of the day, when you have a quantifiers question, they are looking for

What is a guaranteed amount of overlap between two categories? And that's how I usually get to my answers there.

So, we go up and look at more advanced lines. This one barely even makes sense. Okay, I like this one.

We haven't really taken time to do a question, but I'm not seeing any more questions right now. So why don't I just kick this one out to you?

We'll take four minutes and then come back and circle up an answer. And if you feel like sharing your answer choices, you are always welcome to and encouraged to, but no pressure.

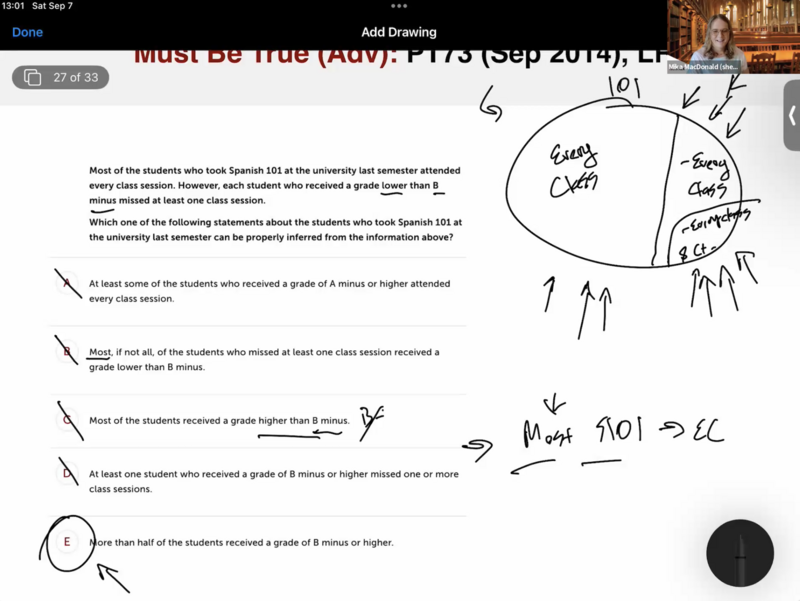

much. You We've got one answer in, take another minute and a half. All right, let's talk about this slide.

The toffee. got two bees and two to three bees, okay. So, let's break it down, most of students who took Spanish 101, all right, so I think our big group is Spanish 101.

Most of them, so let's make it this portion, every class. So, this would be at minimum, not every class, right.

Each student who received a grade lower than b minus. missed at least one class session. So again, I don't know if everyone who missed a class session has a grade lower than b minus, but I do know that everyone who received a grade lower than b minus missed at least one class session.

So for now, I'm going to just represent that as this. So this is the people who have not every class class and who have a grade of c plus or lower.

OK, this is all of the information I have, right? So I'm going to just go ahead and look through the answer choices one by one based on that.

So A, at least some of the students who received a grade of a minus or higher attended every class session.

Well, I can't know that, right? I just know that the people who received grades lower than b minus missed at least one class session.

I don't know if anyone with a higher grade. missed the session or not, right? That is just information I don't have.

Most, if not all of the students who missed at least class session, received a grade lower than B minus.

Again, I can't justify the most, right? Where are we getting that most from? All I know is that if you had a B minus, you missed at least one.

I don't know what percentage of the people who missed classes received a B minus or lower. Okay, see, most of the students received a grade higher than B minus.

So this is attempting one, right? Because I do know that everyone who received a B minus, missed a class, right?

So, the problem there is this says lower than a B minus, this says higher than a B minus, as in this includes B minus, right, or does not include B minus.

But this is people who had a C plus or lower, right? That's the way to, if it is lower than a B minus, that mean is equal to or lower than a C plus.

So C is out. D at least one student who received a grade of B minus or higher missed one or more class sessions.

Again, it is perfectly possible that that did not happen. I just don't know. But I do know E. I do know E, right, because B percent, even if everyone who missed a class had a grade lower than a B minus, that would still be less than 50% of the class, right?

So, I do do know for certain here that most of the people in this class write had a b minus or higher.

Put another way, right? If this is most of 101, this is sum of 101, and this is a sum of a sum, or even a most of a sum, or even an all of a sum, it would still be a sum in relation to the entire class, which means that most people in the class scored a c minus or higher.

That makes sense, everyone? Yeah. So what I use this one as an example, because I just don't see how you take e by doing the most as 101.

Then every class like I don't I don't know how doing it this way could show you the sum of a sum idea that we have here Yeah so This is just if you want to like Understand the Venn diagram approach to quantifiers Google it there are a ton of resources This is kind of the standard way that quantifiers are taught In both data science and in philosophy It's only on the LSAT that people really do this a whole bunch And it's because you know learning it this way is a little bit more complicated, but I think it does pay off a lot If you put in the time All right.

Well, thank you everybody for coming. I appreciate coming to my first my first class of the new cycle I will be back.

think on You I will be back on Friday. I do not remember what my topic is, but I'll be back on Friday of this week.