- Summary

- Transcript

Meeting Purpose

To provide instruction on approaching errors in reasoning (flaw) questions in LSAT Logical Reasoning.

Key Takeaways

- Approach all argument-based LR questions as if they contain flaws, not just flaw questions

- Use an 8-step process for analyzing arguments, with emphasis on "wrestling" with the argument

- Anticipate the flaw before looking at answer choices, using a "just because X doesn't mean Y, here's why" template

- Avoid making assumptions to "help" the argument; instead, identify gaps in reasoning

Topics

Approach to Flaw Questions

- Read stimulus

- Identify if there's an argument (conclusion + support)

- Articulate the argument in your own words

- Wrestle with the argument using the template: "Just because [support] doesn't mean [conclusion], here's why: [reason]"

- Use the reason to formulate an anticipation

- Read question stem

- Compare answer choices to anticipation

- Select best match or eliminate based on anticipation

Importance of "Wrestling" with Arguments

- Take a combative approach to all arguments

- Force yourself to articulate why the argument might be flawed

- This process helps identify gaps between support and conclusion

- Crucial for improving performance across all argument-based questions

Common Mistakes in Approaching Flaw Questions

- Skipping the step of articulating the argument in your own words

- Not taking time to wrestle with the argument before looking at answer choices

- Making assumptions to "help" the argument instead of identifying flaws

- Relying solely on process of elimination instead of anticipation

Time Management

- It's better to do fewer questions thoroughly than to rush through more

- Speed improves with consistent practice of the full analysis process

- Skipping steps (like articulating or wrestling) often leads to incorrect answers

Sample Question Analysis

- Demonstrated the 8-step process on two sample questions

- Showed how wrestling with the argument leads to effective anticipation

- Explained why certain answer choices are incorrect (crimes of commission vs. omission)

Next Steps

- Practice applying the 8-step process to all argument-based LR questions

- Focus on developing the skill of "wrestling" with arguments

- Review additional content on specific flaw types to complement this approach

- Continue to avoid making assumptions when analyzing LSAT arguments

Okay, you hear me? Okay. Thank you.

All right. Yeah. No problem. All right, a few more people coming in. I'd like to see Yeah, but what exams are are you guys trying to take?

Just curious November's exam. Yeah, That's how long you've been studying? Oh, well

Yeah. I failed my first two ones, so this is what I'm gonna take a minute.

Uh-huh. Okay, then we get a November or January. All right, so that's really good to know to get started.

We're just gonna get started, like you guys are here. mean, anybody who isn't, I'm sure we'll have some people joining.

So, here we are. My name is Rob. an instructor at LSAMX. Today, we are going to be in a live class about errors and reasoning, also known as flaws.

I don't think they have any other name, but we're gonna talk to you. We, as like all of us are going to have this discussion about errors and reasoning at the very basic granular level.

Or, um, you know, entry point level. think it's, I really think that the way that you do these flock questions should be the way that you do all of the argument-based questions.

So today I think we're setting some groundwork and a foundation for not just the flock questions, but also strengthening questions, weekend questions, assumption-based questions, and just general reading.

What is unique to a flock question? the surface level, I don't think this is true once you start digging into it, and you guys see why I don't think that's true, but at the surface level, a flock question immediately tells you that what you read is a bad argument, whereas that's not true with any other question type.

Like, you know, a little bit, I think we know that when they ask like, what's the necessary assumption that you think like, okay, there's something that's not said that could make this a little bit better, but-

An argument having an assumption doesn't necessarily make it a really bad argument. Like most arguments that people have in real life contain assumptions and they contain assumptions, you know, because the people who are making those arguments are dumb, but instead because some things are so obvious that they don't even have to say them.

Flaws, on the other hand, I noticed that when test takers in the beginning stages of their okay, I am reading the stimulus knowing that something is wrong with it.

Oh, great. Now I can really dig into it. You should be reading everything like that. Like a strength in question and a flaw questionnaire.

They're the same. You know, we can question a flaw question. They're the same. So what we learned today, like the attitude of going in knowing that what you're reading is a little bit wrong in some way, I want you to take that attitude and that technique and apply it to all of the argument-based questions.

questions. So we'll talk about a little bit about what that looks like, and then we'll do some problems. It should be a pretty easy day here.

All right, so let me show my screen connected via cable, and we're on should look something like this. All right, you guys see the screen.

I think we're ready to go. Okay, so any questions, comments, any, you know, general concerns, feel free to feel free to throw that in the chat.

But, you know, in in live classes where there's not that many of you, I tend to want to reward those of you who show up for them.

So, you know, I have a much higher tolerance for questions being asked out loud, like that's generally pretty chill when there's only a couple of you here.

As long as you like, you know, raise your hand. or something, and don't talk over me. All right, so here's what I would describe as the approach to flock questions.

OK, so first thing I want you guys to do. It's you know it's a flock question. Why? Because you read the question stem, or because every argument is kind of the same as a flock question, we're not going to really dig into that now.

But you may talk about that a little bit later. First thing that you want to do is read the stimulus.

OK, that's not rocket science. That you're not going to give every four of you, don't do that. OK, what happens after you read the stimulus?

Anybody know? here's you stimulus. So, I remember when I was in high school and I had a professor or like a teacher that goes to history or maybe an English teacher, and he was describing the steps to writing a paper.

He's like, okay, you know, like step one, you know, you brainstorm, step two, you know, you outline step three, you draft it, but you know, just trying to fill in as much as you can.

Step four, you go back and revise it, step five, you edit it, six, you like send another draft in.

And he's like, most of you just have a two-step process and it's just called writing the paper. So I think of that for Elsa.

So it is actually important to parse out what these steps are instead of saying like, one, read stimulus, two, answer the question, like that's not helpful, that doesn't give you implementable strategy, just like repeats like the single most obvious thing about any test taking or question answering experience ever.

So, What is unique to the L set, you're going to read a stimulus. Now, step two is, is what?

Okay, let's step two, because not every LSAT stimulus in logical reasoning is an argument. You have, you have different kinds of things going on.

might have a must be true, a must be true. just like a set of premises. There's no conclusion. You know, you have the argument exchange or there's just like two people talking.

Usually they're making arguments. Sometimes, you know, they're in outer space. face, you know, in a world where like the laws of physics or English or, you know, argument and formal logic like simply don't apply to them.

Or you may read, I don't know, you know, what else can you read that where there's not an argument?

Not a whole lot, honestly. So first, like, you decide whether there is an argument. How do you know if which, you know, this is really kind of wrapped up in step two, I will say, identify the argument.

Okay. What does it mean to identify an argument? Does it mean that you say, like, that's it? Like, that's, that's the argument.

An argument has two parts to it. Those two parts are conclusion and piece of support. The argument argument is not just the conclusion now that sounds like it doesn't matter and then I'm making like some like very like academic or semantic distinction between an argument and a conclusion but it does matter because when you do a strength in question for example the way that you strengthen an argument is you strengthen link between the support and the conclusion you can't support it you know like you the argument is the connection between the support and conclusion the quality of an argument is like very simply the quality of the connection between the support and the conclusion so when you are identifying an argument you are doing two things you're saying this is the conclusion and this is the thing that's supporting it yeah yeah it's here

Inclusion, the support. Pretty simple, right? Once you've identified it, some of these, like these steps are pretty fluid in real time.

We'll take a look at some of these. What do you do after you identify the argument? When I'm breaking this down into like 100 steps, you know, like, I don't expect you guys to write down all these, but there is a process, and the process isn't just like read the stimulus, identify conclusion, and then just like go to the answer choices.

Like that's what, I think that's what probably most test takers scoring, I don't know, scoring under 160, I think that's probably what most test takers are doing.

That might be like a little harsh, but probably another instruction. You'd be like, oh, 152, 155. You know, like, we're going to have different marks than that.

Depends how skeptical you are. And then you articulate the argument. And what does that mean? Just answer my own question.

If you cannot explain something in your own words, you don't know what you read. So like, what step four is, is a check to make sure that your step three was actually as good as you think it is, because sometimes you can just identify something, but you don't really know what it means.

So I'd be like, that is the argument. the first sentence is the conclusion, the second sentence is the support.

That tells me that you don't understand it. But when you say, well, the conclusion is that Einstein is amazing.

scientists and the support is that, you know, he won a Nobel Prize and, you know, fundamentally change in nature of physics.

Okay, now I think you get it. You know, sometimes with like very, very short arguments, it's hard to have a lot of flexibility outside the words because the other conclusion that's just like two words, you know, they'll be like, or something like, this man is wrong.

Like, you know, the world is not flat. Like, how do you articulate that in your own words? You can't.

You just have to take that and be like, uh, that's what it is. But this is a big, big test to see if you understand the argument.

And if you don't understand the argument, was going to make five, step five, very, very difficult. And step four is something that's going to help you across the board in the LSAT, like not just flawed questions, not just in argument-based questions, but, you know, in must-be-truth, in reading comprehension, when you get to law school, probably when

when you're after about school, but that's something I can't really weigh in on. This is a useful way of thinking about the stuff that you're reading.

We know it. I know so many times when I was studying for the LSAT, I would kind of like lie to myself because I wouldn't be able to do very number four very well.

And I'd be like, ah, I get it. I get it. just can't explain it. I didn't get it. You know, if you find yourself in that position, like, ah, I get it good enough.

Like, I couldn't really explain it to a 10 year old, but I understand it. You are wrong about that.

So look in the mirror, like it happens to us all, but I didn't understand it. Even if you get a question right, yeah, ahead question.

So what do you do if like, time is against you? And you kind of get the logistics, but you don't like what you do, just skip it.

That's question to you, like, like, what do you mean, like it which step in the process? So for example, right?

go ahead. Like step four, for example, right? You see you mentioned earlier that, like, I kind of care what they're talking about, but like, um, but what if like you kind of get it, but really like, like you lie to yourself that you get it, but then like, yeah, some trick, what do you do?

Like, cause there's, there's some paragraphs that are like, we have to like go back, like, wait, we time out.

And then I might see some like words that I don't really, the question were kind of the answer were kind of related to it.

But then there might be one of those two words, like very or all that, like, it cannot be answered.

But I'm like, I think that's where I'm struggling. Like, I'm always stuck between two answers.

And I'm like I'll show which one of these are most likely to be wrong okay a couple things in your one Take you know to dig into the first part of question is there there's a lot Like this this is kind of like the crux of of it all right like we have a clock that's running We don't have infinite time, you know, so it's something you're thinking about all the time you can't skip step four and Like you can't say like oh like I'm running a long time like I'm not really do step four because if you can't do step four your odds of like navigating the answer choices to find something that is correct are super low Especially like once you get out of the first 12 questions in L.R.

And You can't do number four. You have almost no chance of getting that correct So like if not as if you can skip it and then be like ah cut a little bit of time

I'll be like a little bit, you know, unprepared, but it's all right. It's like, if you cut out number four, you might as well not do the problem at all, you know, which means like, but you've already invested in this time, it's more like when you are managing time on logical reasoning, there's a certain amount of time that needs to be invested into every question in order to have a chance doing it.

And a lot of test takers, like when you're early in your process, say it takes you two and a half minutes to do a question.

Now obviously two and a half minutes times 25 questions is like well over the amount of time that you have to do the exam.

So like what do you do? you just start doing questions in one and a half minutes? No, because if you need two and a half minutes, one and a half minutes is you can't operate like that.

You know, it's not like, it's not like you're operating at like 60% capacity. It's like you didn't take you didn't take this.

step to be guests in your car. You can't drive it. know, like, it doesn't. Step four is putting gas in the car.

So the reality is like, however long it takes you to do a question, you're just, you're kind of stuck with that.

And, you know, you can live with not answering all the questions in L.R. Like, that's, that's totally okay. I mean, what I'd recommend is that you follow this process on like the first 12, the first 15, see where it gets you, and then just kind of like, you know, see how you're doing on the rest of it.

Because the more you do this process, the faster it's going to get. So like, ultimately, over time, you know, week after week, like that is the thing that's enabling you to like beat the clock.

So it's a, you know, it's a good question. You know, being, you know, the next part of the question, something I talked about little bit, uh, everybody thinks that you're in this, they're like, what do you do?

When I'm like between two choices, it's like, like, what do you mean? Like everybody's between two choices. Like that is the nature of it a lot of the time.

Like nobody ever says I was between three choices. Nobody says I had only one choice left because you either that's either right or wrong.

Like you always are between two choices. If you didn't really understand what you read my general. So like it's not like a unique phenomenon.

It's something that happens like literally every time you get a question wrong. That's probably happening like 80% of it.

Here's what you should do if you're between two. Don't pick something you don't understand. Don't pick something because it sounds more sophisticated.

And if you find something that matches your anticipation, pick that and move on and don't ever read the other ones.

All right. Yeah. So once you've articulated the argument, now what do we do? Now, do you want to look question?

Now, do you read it? The answer is no. Okay. So, if, yeah, I mean, this particular instructor that I'm about to reference is not actively tutoring with us right now.

But he used to have this saying, when you do LR, it's like, you want to be a jerk. You know, he wants you guys to read arguments like you absolutely hate the author.

Like, you're just looking to rip it apart. Like, doesn't matter what they say, you hate this person so much that you're just going to take that contrarian approach and you're going be like, you know what, going disagree with you just for the sake of disagreeing with you.

I'm going to find a hole in this argument just to annoy you. That will get you very far in LR.

Like, it's a really good strategy. a little bit uncomfortable for those of us who aren't at. I was conflict oriented, but that is how you should do the Elsa.

I've phrased this a different way, which is just wrestle with the argument. So you need to understand where the argument is weak before you look at the answer choices before you're like, okay, how do I strengthen it?

You don't want to be in a situation where you think, okay, I have to strengthen an argument. What's wrong with the argument?

Oh, the argument seems perfectly good to me. You will not be able to strengthen an argument that you think is good.

You will not be able to find the flaw in an argument that you think is good. So this step five enables you to wrestle with the argument to find the weak points.

And then once you have that weak point, that's the thing that you use to help you answer the question.

Like it's kind of like one of the weird secrets of the Elsa. I'll ask test takers to say, well, what do you think of the argument?

And a lot of times people say, well, it doesn't matter what I think. It just It's matters that I do what I'm supposed to do.

It's like, well, it actually doesn't matter what you think, because the whole test is set up to examine how well you understand the weakness in the argument.

It's like it does matter what you think. That's actually the only thing that's being tested in like 60% of the LR questions.

So you wrestle with the argument, I'm going to give you a template for this that make this really easy.

There's a couple of different ways to do it, but today we're going to look at this way. Oh, whoops.

That's not right. Here we go. Okay, so we can all read this, all right, just because support doesn't mean conclusion.

Here's why. All right. So we have an argument. Yeah, is that even, I don't think that's, I'm pretty sure that's true, I actually don't know if that's true, if so, when did he win it, was it like 10 years?

Okay. Here's an argument. What's the conclusion? What's the support? What's not using nonsense color? So here's what we're doing.

We're doing this whole process. Step one, we read the stimulus. It's amazing because you want to know what price.

We read it. Awesome. You guys are not often going to forget the first step. think you guys do really well with that.

We identify that there is an argument because we can see a conclusion in support. We're identifying the argument. The conclusion is that Einstein is an amazing scientist.

The support is that he want to know what price. Explain the argument in our own words is very hard to do with something that's this short.

Usually when you have more difficult, like a more difficult stimulus, where the conclusion isn't explicit, that's when it pays to explain it your own words a lot more.

in this. In this case, like explaining our words is like, well, the conclusion is that, you know, makes things really good in science.

And the support is that, you know, he won something that is, like he won a prize, that prize is a Nobel prize.

I'm kind of saying something. Now, I wrestle with the argument. Okay, so good. Just because support doesn't mean conclusion, here's why reason.

So, just because Einstein won a Nobel prize doesn't mean he's an amazing scientist. Here's why. Can you guys think of a here's why for that?

Anything? Anything at all? at that point. That's harsh. That's bad. Maybe like a real. I'm sorry, um Anybody got to hear is why?

Can anybody tell me like give any reason why like what's weak about this argument? Okay, someone's coming in No, about that You know like that's that's just not there.

We go. There we go. There we go now. We got a good answer Okay So let's see what what can our reason be So our reason could be anything Our reason could be Nobel Prizes Or given to people randomly

Okay, here, that's one, right? Okay, here's two. This is, this one's a little sloppy honestly, being amazing means that you need two Nobel Nobel prizes, kind of a silly concept, Nobel prize is like weirdly like a lifetime achievement award that's like given for a particular contribution, it's like, it's kind of weird.

For science, that's not really true in my literature or something. Anything else? What about this? His Nobel prize? was in literature right like I could do another one I guess you also want to know what prize in literature Bob Dylan okay so Joseph's comment doesn't actually weaken uh is that me you know why oh no you know what that's totally right I like to call you out and then I right

Sorry, that's like such a yeah call out and it's like well what you said is actually correct. Yeah, if if you had said something like you know if you gave the name of somebody and then said this person's an amazing scientist but they didn't win the Nobel Prize that wouldn't work.

And I think you guys understand why. But if not we're not going to dig into that too much. Right, like if you ever gave a Nobel Prize to somebody who's not amazing, then this argument doesn't really make sense does it?

Like the conclusion still might be true. It's just like that support is insufficient for it. You know, that's that's where you want to get.

So when we've wrestled with the argument, we've found a lot of different ways to break the length between a Nobel Prize and a scientist, an amazing scientist.

Like it all comes down to How do we know that a Nobel Prize is an indicator of amazingness in science?

How do we know that? don't from the stimulus. That is the problem with this argument and We figured that out by doing this little template that just because support doesn't mean conclusion.

Here's why reason You will get very very far If you do this on the outside if you just do this template Like that's probably I mean, I think Yeah, it's I would I would strongly recommend doing this Some of these you might look at our answers and be like well, do you rub?

you really think like? You know the correct answer is gonna talk about Bob Dylan. No, no, don't So it's like this is a very like a highly specific anticipation that you're probably not gonna see This is maybe a look

closer to something you might see, you know, but like they're all different ways of like opening your mind to the idea that the correct answer is going to be something that says no well prize.

What does that have to do with amazing? That's what it wants to do. So that is when you, that's what you do when you wrestle with your argument.

It allows you to see what's wrong with it. And then with that piece of information, like you read questions down, figure out what, you know, you're being asked to do, okay, and use the the reason to formulate your anticipation.

Right, and then after that, it's like, what's step eight? know what mean? Like, OK, this gets to, like, you know, we start getting deep here, right?

You know, if you see it, what do you do? If you see your answer choice, you pick it. If not, what do you do?

That's for another class, not for today. like, there's your, that's your, like, eight part how to do argument-based questions.

Notice how that's not actually specific to errors and reasoning or flaws. But, like, that's it. That's what I want you guys to do.

If you practice doing this, you, I mean, you're going to see a lot of improvement. And the critical... point of this.

I think the stuff like where you're really going to see a lot of benefit is here. And here. And just for the reason that number five is going to be very hard to do if you can't like that's that's what this looks like.

I would say, you know, in your preparation over the next couple weeks, either write this down or screenshot it and then print it off or something.

And then every single LR question that you do. Do it like this. So notice if you're doing a must be true.

And you've identified like if you haven't, if you read the stimulus and you're like, this isn't an argument. Well, then this step two is going to be your last step, you know.

Oh, like, must be true would be the first two steps and then a whole another chain, which we're not going to get into.

And it's like, it's not eight steps long. It's like four, but this is, this is all it's going to help you so much.

Like wrestling with the argument, taking that combative approach is what really, really makes the difference. Like you are not becoming, you're not becoming a lawyer to agree with people.

You thought that that's not going to have them. So you can't be like, I think that's a good argument.

You know, you just, you have to go after it no matter what. And forcing yourself to, like a lot of people kind of just do like the, oh, yeah, it's a bad argument.

Yeah, like that conclusion just doesn't make sense. Like you haven't done anything. All you've said is it's a bad argument, but you already know it's a bad argument.

So you did nothing. You just like repeated like the, the basic concept of a flaw question. Pushing yourself to say, here's why and coming up with a reason is going to push you to articulate the problem with your argument.

Like that's gonna, I mean, it's gonna be worth it so much more than like spending your time, you know, absurdly, you know, canvassing answer choices and hoping that something sticks, it's not gonna stick.

This is what you do. So I'm gonna see this in action. Right, that's gonna kick out. That's a little glitch in the matrix, okay.

700 questions. How many can we do in 20 minutes? Let's do this. Okay, by the way, guys, don't say this a whole lot but if you guys, answer the question.

before I'm reading the stimulus. Please don't do that. If you continue to do it, we might not be allowed to be on these, because it's experience for everybody else watching.

The more modern archaeologists learn about Mayan civilization, the better they understand its intellectual achievements. Not only were numerous scientific observations and predictions made by Mayan astronomers, but the people in general seem to have had a strong grasp of sophisticated mathematical concepts.

We know this from the fact that the writings of the Mayan religious scribes exhibit a high degree of mathematical competence.

Okay, so do we have an argument here? Is there a conclusion? Is there something that being said by support?

Any kind of proposition that that we have to just try to support the eyewitnesses. So what is the conclusion?

The conclusion is that the Mayan people, in general, seem to have had a strong grasp of sophisticated mathematical concepts.

And what's the support from that? The writings of the Mayan religious tribes exhibit a high degree mathematical competence. So what's next on our list?

Like we've identified the argument, now we're gonna articulate it in our words. Basically what we're looking at here is, the conclusion is that the Mayan people knew math really well, and the support for that is that the Mayan religious scribes knew math really well.

Now let's wrestle with the argument. So just because support doesn't make conclusion, here's why, just because, and you guys feel free to provide the here's why.

just because the Mayan religious scribes new math really well doesn't mean the Mayan people in general knew math really well here's why you guys tell me why that just like this is a good argument I guess I get to do is come up with some here's right you guys were really good on the Einstein one okay here we go now you're kind of okay so the first response the first response to

is not provide a reason. So if I go through this just because the Mayan scribes new math doesn't mean that the people in general new math, you can't say, oh, the reason is that the people might not have a concept of math.

Like, that doesn't address the weakness in the argument. That just disagrees. All you're saying there is like, I think maybe the conclusion might not be true.

But you're not explaining why. Like, why do we have any indicator? Why would there be a reason that describes new math that the people didn't?

Is there any kind of reason? OK, so one argument in the chat, only the scribes were trained in math.

OK, now that's a good argument. Or like, that's a good reason. Right, let's see if we put that one in the template.

OK, just because the Mayan scribes new math doesn't mean that people in general new math, here's why. only describes we're trained enough.

Does that make sense? Like, yeah, that, that, like, that really, you know, gives us a reason why this might not be true.

So if you take the next step and you're thinking, okay, I have that little reason and the reason is, like, only describes we're trained in math.

Like, obviously, the scribes have some sort of mathematical competency. It, like, it is possible in society for the scribes to have some kind of mathematical competency that the general people don't.

One of the reasons is that only the scribes were trained. Another reason is that, like, there was, like, you know, 10 people who had like an innate concept of math and they're like, you get to be a scribe, you know, even though they didn't base, it's got to be something like that.

So then we see, like, okay, this argument's vulnerable. we're looking for a flaw. We're going to use that reason to formulate an anticipation.

We're looking for something that has a meaningful distinction to show that the scribes could have gotten math knowledge, whereas the general people did not get math knowledge.

Where do we see that in the answer, Trices? It's a little tricky because it doesn't go right with the words, it takes a little more abstract approach.

Okay, yeah, yeah, B. Yeah, so we have like a generalization, we have a sample that's unlikely to be represented, right?

no one thinks that what the religious scribes in a civilization do is a good indication of what everybody in the civilization does.

Like that might not be right. Like even if you said the religious scribes eat three meals a day. For the religious scribes, you know, put on their pants one night at a time, like I would still be like, you know, I don't know, I don't know, if the regular people do that.

I don't have any any evidence. You know, in this text attempt with the regular people like that suggests that describes lifestyle and behavior and technical mathematical knowledge is indicative of what everybody else is like, there's, there's nothing there.

So we pick B and, and we're good. The last thing in the chat does not really provide a reason.

Because the writings of the scribes, well, they display or exhibit a high degree of sophistication. If the stimulus isn't telling us that the scribes are saying that everybody had that like my my guess.

Like if the stimulus said we know this from the fact that. but they're right into the mind scribes, tell us that everybody knew math really well, then your thing would make sense.

You're like, yeah, like that's just their perspective. Like they just wanted to make themselves sound good, but they didn't know or they lied.

So we got bigger. All right, let's see if we get something a little. I don't like that. Let's get something like this maybe.

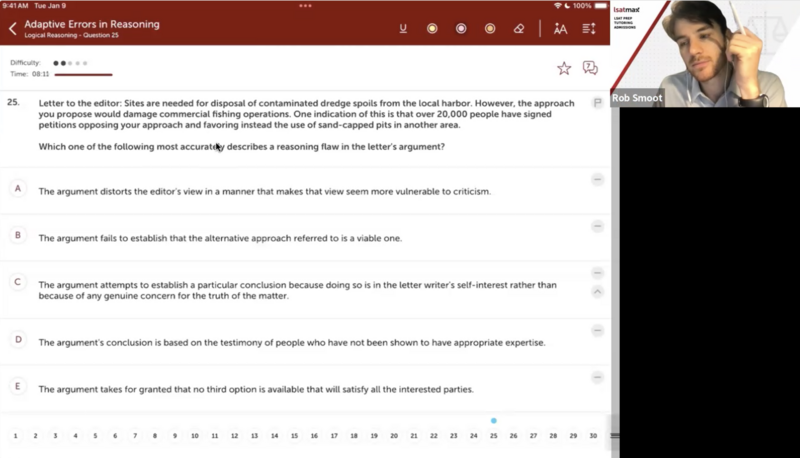

Okay, let's try it again. Take it from the beginning. Letter to the editor, sites are needed for disposal of contaminated dredged soils from the local harbor.

However, the approach you propose with damage commercial fishing operations, one indication of this is that over 20,000 people have signed petitions opposing your approach in favoring instead the use of sand.

gap pits in another area. Okay, is this an argument? Yeah. How do we know that? Well, the letter is examining an editor's position and criticizing it.

When you're criticizing somebody's position, you are making an argument on the LSAP. It's really not totally true in real life.

So, what is the argument? The approach you propose with damaged commercial fishing operations, the support is that 20,000 people signed a petition opposing the approach and favoring a different approach.

So, if we put this, you know, we articulated it on the words, make sure we got this. So, the, the, basically, the conclusion is that this proposal hurts

commercial fishing. Why? Because 20,000 people signed a letter that they didn't like the approach. Now, this argument like you got, this is where you go right in the step five, you wrestle with it.

Just because 20,000 people signed a letter in opposition does not mean the approach hurts commercial fishing. Here's why. Are these 20,000 people commercial fishermen?

Like that's the very first question I would add. If 20,000 commercial fishermen signed that approach, that's actually probably good evidence.

If 20,000 people who are like business developers or 20,000 people who have personal vendetta against commercial fishermen signed a letter, that's not a good argument.

What if these 20,000 people are just really dumb? What if these 20,000 people are doing it for like some kind of like habitat thing, like they want to like.

like they want to save the salmon or something and it actually the proposal would help commercial fishing it would be like awesome for commercial fishing but these people hate them or something you know like that's what you want to dredge up in this one yeah like there's there's just no there's no link between who these twenty thousand people are there's no link between why they they oppose the approach I don't know why sand cap pits like what kind of environmental commercial fishing effect that has like you see that like the stimulus doesn't link anything like because 20,000 people signed something it's like ah I can't think of a worse reason not to do something it just it's just so meanings so we read the question of that which describes a reasoning thought we take our reason our reason is that well

The 20,000 people, how do I, you know, like they basically don't even have anything to do with commercial fishing.

Like they probably don't, you know, if the argument, if these are 20,000 commercial fishermen, then the argument's probably a lot, probably really good.

If these 20,000 people are anything other commercial fishermen, I don't think this argument's good. So we look for something that is suggestive of that.

Like that's our anticipation. We use the reason to build our anticipation. For those of you who are like, yeah, anticipating is really hard, don't really know how to do it.

I feel like I'm bad at it. Use this template, wrestle with the argument, and then you have like this little nugget that forms your anticipation.

Like that's how you get it. Like you can't just create an anticipation of a thin air when you haven't wrestled with the argument.

It's like, that's like what we don't tell you until now. So now that we have that. argument, we have have have argument argument argument argument argument

let's go. All right, what do you think of Ag? No, no, oh, so close. Okay, someone is correct. is D.

Okay, to answer the thing in the chat, no, we cannot assume from the context that 20,000 people are commercial fishing that.

Okay, I'm going to address this because, like, this is probably like one of the, one of the best questions that somebody's like ever asked in terms of LSAT studying.

If you We're like, do not make any assumption, ever, unless the test tells you to assume something. You know, when you talk to a little kid, you have to like, explicate the entire argument.

Like, you have to say like, we shouldn't do this because it's a bad idea. And we should never do bad ideas.

Like, that's how you talk to a kid. When you talk to, no one talks to an adult that way, why?

Because it's condescending to talk to an adult that way. So when you talk to an adult, you're like, we shouldn't do this.

It's a bad idea. When you talk to a little kid, you know, we shouldn't do this because it's a bad idea and we should never do bad ideas.

But that last part that we should never do bad ideas is an assumption. When you're talking to the adult, and you say, we shouldn't do this because it's a bad idea.

The assumption is that we and do things that are bad ideas. So in real life, you are free in conversation to pick up on the assumptions that people are putting down in their conversation, because it's just going to make conversation easier and less condescending.

you know, like that's what adult conversation is like on the LSAT. If the author doesn't explain to you like you're a little kid, there's a flaw in the argument.

So like, don't do work for the author. Don't, you know, be like, oh, I see what your assumption is.

I'll just, I'll let that one fly because it's obvious what you meant. No. If they don't connect everything for you, you seize on it.

You say, that's the problem and you attack it. Like that, but it's like that's, that's like why some people like really struggle with assumptions because your brain is automatically making them because, you know, living in everyday society like requires you.

Like if every day society you walked around like you did in the outside you just you wouldn't be able to understand anything Like you'd be like all that doesn't make sense.

It's like well, it does There's just like a pile of assumptions and what that person said on the outside It's your duty to say like to like make your brain stop Automatically working for the author and take a combative approach and be like that's that's unfinished.

You didn't give me them So that just to answer that question. So the answer here Like notice like if you assume that Then now there's no law in the argument So like you can't answer the question if you like you've you've helped the author so much That you no longer can answer the question like that's that's what happens if you make assumptions when you're not asked to do so on the outside So it's D You

The problem that we showed, like the anticipation that we had and the reason was like these 20,000 people, I don't even know if they're a commercial fisherman.

I don't even know if they have any interest in commercial fishing, like that's the problem. You just 20,000 random people.

That doesn't tell me what you want to tell me. So, it is the testimony of 20,000 people who have not been shown to have the appropriate expertise and that's expertise in knowing whether something would damage commercial fishing operations.

That's my D is correct. Now, C is wrong. Here's a couple. Here's one reason why C is wrong. Like the high level thing why C is wrong is that it doesn't look like anything close to our anticipation and you should have read C looked at that be like that's not.

That's not the anticipation that we formulated based on the reason. So, like I'm not. Not even good. I'm not even going to deal with it.

And then you read D and you're like, I love D and you select D. Like, that's what your process should look like on a on a more specific street level view.

Why is he wrong? There's no indication of the writer's self interest. I don't know. mean, you're writing a letter to the editor.

If this, I mean, if the writer was a party affected by this, and the stimulus gave you a hint that there was like some extreme bias, you get a little closer to see, but you still can't pick see because you'd have to show that there's no genuine.

You and concern for the truth of the matter like it's they're just the elements that we see an antitrust C Are just like no where to be found in this thing like it's not that C commits a crime It's that C omits Anything relevant to the answer you know answer choice can be wrong for two reasons there can be either crimes of commission or crimes of omission and And a crime of commission is like when you read the stimulus and you're like that thing that or when you read the answer Trusting like that thing that the answer choice said is wrong and contradicts something in the stimulus like it just it just It's wrong The other time when it's crimes of omission is like when you look at an answer trust you're like there's nothing in this It's wrong.

It's just the problem is There's nothing in it that's even right like there's nothing in it. even tethered to any analysis So when you guys do

So, crimes of omission are a little harder to spot for people when you don't anticipate, like when you anticipate a crime of omission is really easy because you look at something you're like, that doesn't look at all like my anticipations, that's unlikely to be right.

But if you are doing process of elimination, the process of elimination approach is like you guys look at an answer choice and you should not do the process of elimination approach.

I think one of them about to say makes this clear, but like just to say that up front, you do the anticipation approach, not the process of elimination approach.

It doesn't work. You won't get better if you do that. If you do that, what normally happens is people will read an answer choice and they'll say like, okay, this answer choice is wrong because X.

This answer choice is wrong because Y. This answer choice is wrong because Z. And then you get to something like Z and you're like, I can't figure out why C is wrong because it doesn't directly violate anything in this case.

stimulus. And the answer is like, well, C just doesn't even interact with the with the stimulus enough for it to contradict anything.

So if you're looking for contradictions in order to eliminate something, you're not, you have a hard time rusting the state.

But the reality is like C is wrong because it's nothing in C, you know, is relevant at all to the stimulus.

But that's what makes it a really tricky answer choice to eliminate. So like, that's, that's the process that, you know, one of the inherent problems with the process of elimination approaches, like you get something like C and you're like, yeah.

Yeah, let me go like throw a little thumbs up on the comment in the chat. Great. Yeah, another good question in the chat, like, is this like a

sampling error? Maybe? I mean, you know, what we saw in the last question is that, you know, there, the author is trying to use, you know, one group that wasn't really representative, or there were like concerns about how representative was.

And in this, I guess, you know, at the, at the high level, you could say that we're using a group that, like, maybe isn't representative of the people who would knowledgeably be able to tell you that it damaged commercial fishing operations.

So like, yeah, but I don't know, I get uncomfortable with going at a sampling law. I don't think that this would, this is a, it's like, this is an appeal to authority law, not a sampling law, in technicality, which brings us to the very last point that I want to make.

You notice how I haven't named any of the flaws in this hour. That doesn't mean I don't think you should not learn them.

It just means that I think I want you guys to work in this space. If you do these eight things, you are gonna develop like a really, really good method that once you start knowing what the flaws are called and how to spot them and you're gonna get even better at it.

But I don't think, like if you're just trying to memorize flaws, but you're not doing step five here, you it's a harder road to get there.

But certainly I've done a lot of errors in live classes. This is probably like the most different. This the only one where I've never like directly named flaws.

I do think that they're important. I would encourage you to. kind of watch some of the other ones that I've done where I talk like in greater detail about like what I think you are the 10 or 12 flaws that you need to know on the LSAT and give you examples of them and all that.

Like that's a really good companion piece to this. That content like that is going to be from like, yeah, I'm going to say like late February or maybe early, I'm not going to say late February of 2023 is where you're going to see like, you know, me do like an hour and a half and just tell you what I think like the 12 flaws worth knowing are because I don't think there's like 33 common flaws like that.

That's like always really funny to me. 33 common flaws, Well, here's the thing. the last question on Joseph's comment here.

It's like, well, you guys are hitting at the root of what like you're kind of like on the edges of like really understanding what the LSAT is all about.

Like every argument is flawed because it contains an assumption. And the assumption is always like the author thinks that there's a piece of knowledge that's obvious, but like we don't actually know it.

So when you say there's not enough information to know, it's like that's technically how every assumption based strength and we can flock question works.

Like you could say that for every single one. So it's like, it's not specific enough, but you're like really on the right track just in thinking about it like that.

But in terms of the second. part of the comment. We're saying like, what if there's only, you know, 20,000 people in the town?

Well, how does all that proves is that everyone in the town doesn't want to do this. That doesn't prove that it damages commercial fishing.

It proves that it's wildly unpopular. Like, you still haven't connected the citizenry's, you know, petition to anything that's related to commercial fishing.

So, like, there's, we still have the same problem on a specific level. But on the grand level, ultimately, like, there's always a gap between the support and the conclusion on the LSAT.

And when you guys wrestle with the argument, it helps you find that gap. And the only thing that the test cares about is that have this and you go.

So, you guys have been great. Thanks for the participation. You know, we're hanging in. Yeah, oh, yeah, I kind of agree.

I think that's fair. Joseph, I think that that's a good point. Alright, I'll see you guys later. I'm either on.

I think I went tomorrow, actually. Alright.