- Summary

- Transcript

Meeting Purpose

Review principle (strengthen) questions for LSAT logical reasoning

Key Takeaways

- Principle questions are essentially strengthen questions, focusing on general premises that bridge specific claims

- Key skill is identifying missing general premises that make arguments valid, often in conditional "if-then" form

- Don't question truth of given premises; focus on logical structure and bridging gaps between premises and conclusions

Topics

LSAT Format Changes

- Logic games section removed from future tests

- New format: 2 logical reasoning, 1 reading comprehension, 1 experimental (unscored) section

- Experimental section indistinguishable from scored sections; all must be taken seriously

Principles and General vs. Specific Claims

- Principles are general in scope, not specific to individuals/instances

- Arguments typically follow structure: specific premise -> general premise -> specific conclusion

- General premises often missing; key to identifying logical gaps

Strengthening Arguments

- Focus on bridging gap between given premises and conclusion

- Don't question truth of given premises; assume they're true for argument's sake

- Often requires adding conditional "if-then" statement connecting premise to conclusion

Practice Question Walkthrough

- Demonstrated process of identifying missing general premise

- Emphasized importance of focusing on logical structure rather than real-world plausibility

Next Steps

- Practice identifying missing general premises in arguments

- Focus on "connector dots" approach to principle/strengthen questions

- Review older LSAT tests, as difficulty level remains consistent over time

How's it going? Good, good. Thanks, Richardson. Oh, let's let me know what you want me to call. For any of you, let me know if I call you the wrong name or mispronounce the name.

I often kind of guess off whatever it says on the zoom card, but that's not always the right thing to do.

So if I make a mistake, feel free to correct me. Okay, so I'm going to. give me another minute or something for people to join before we get started like fully but if anyone has any questions about anything they should feel free to shoot right now and I'm happy to address them while we maybe give another 60 seconds for people to join.

you you That's right, there's no more logic games. That is correct, for all future tests. Actually, it's a kind of vice, and not funny, it's an interesting story as to why that is, but you guys are curious, I could explain it.

But functionally speaking, there's no logic games. Now the test is three sections that are graded, two reasons sections, and one reading comprehension section.

There will still be a four-foot section on the test when you sit for it, the experimental information, you can't predict what it's going to be, will be experimental, and therefore not count towards your grades.

It'll either be a third logical reasoning section or a second reading comp. Again, no way predict that. My guess would be two-thirds of the time it's another logical reasoning section, one-third of the time it's another reading comp.

That's two of it for a couple of different reasons, but yep. What you're graded on is always two-watch reasoning and one reading comp.

That will never change. You may have to take either a third-watch reasoning section or a second reading comp. Reheption section.

When you separate the test. And you don't know if you're going to do that. That's the big thing. No.

So you have to take all four sections seriously. But, um, equally seriously. Like they're the real test. No, there's no correlation at all.

In fact, you should expect it to be basically the same. The only thing that, the only correlation if you wanted to insist on trying to find one would be something like it's probably more, it's probably more likely.

then your average section is to be, to be essentially trying to find the best way to put this. It's more likely than your average section to be, sorry, the word I keep wanting to say is unfair.

That isn't quite the right way to put it. Here's what's actually going on, so you know exactly what's happening.

The questions that are giving you on the session are questions they're planning to use on future LSATs. Not only that, they're questions that have already gone through quite substantial internal drafting and review.

So they're very close to finalized LSAT questions. This is a final experimental control on difficulty. So the whole point of the section is to collecting data on your performance on that section.

But the only way that data is useful is if a number of things are true. One, they're treating that section the exact same way you treated them.

real test, which you have to by design because you don't know which one it is to if they have reliable data on how well you're doing on already controlled for and official questions, which they do because they can measure your performance on the rest of the test.

So essentially what they end up doing is they compare how everyone who sits for the real test does on the external section compared to how they did on the other sections that they just sat for.

And if they do it by question by question too. if any question basically ends up consistently either being easier than they thought it would be or harder than they thought it would be measured by people's actual performance, then they can adjust the difficulty.

More importantly, they more importantly they often don't adjust the questions themselves. They're trying to get a precise gauge of difficulty so they know how to set the scoring curve on future exams.

Okay, so essentially though there's no you should think there's no difference. experimental section is identical to any other section.

There's just a slightly higher chance that one or two questions will be not perfectly worded. and need to either be reworked or scrapped entirely.

does happen. Like a slight ambiguity that they missed in wording might lead them to conclude later. Actually, that isn't a perfectly objective or fair question.

But their standards for objectivity and fairness are outrageously high already. So it doesn't happen often and it'll happen to a question that is, you know, like, by and large, that's how that's how you should take that.

Okay, any other questions before we start? How's everyone doing? How's everyone feeling today? How's studying been going for people?

I think that's probably not only reasonable, but also quite common sentiment on this test. Okay, so let's start. So first I guess I see some new faces here today.

So I might as well go over some ground rules. My name is Lewis. I'm a tutor at LSAT Max.

These live classes, we used to call them office hours, live classes is probably closer to what they really are, but they're like somewhere in between a lecture, a seminar and a video lesson.

They're kind of drawing a little on all of these concepts. serve multiple purposes as well. One purpose of these classes is to give you guys some facetime tutor outside of one-on-one tutoring.

So that's part of what this is. And to that end, if any of you guys have any questions, about any topic, not even.

They don't have to only be related to the subject. You should feel free to ask me, especially at the beginning and at the end.

I'll set aside time for that. Now second, they're designed to be supplements for the sort of core curriculum, right?

So what that ends up meaning in practice is, you know, you're going to say, suppose you're going to the video lessons, and you're not entirely sure what to make of something, have some questions, whatever it is, well, one of the ways you can use these live classes, I guess, is you can go look at, okay, well, how did this guy, in this case, me approach these things, and then you can sort of supplement your understanding that way, right?

So oftentimes, different test takers, even very good test takers will approach the test very differently from. each other. It's, I think, incredibly helpful if you're studying the all-side-over and extended period of time to expose yourself to multiple different approaches, multiple different personalities until you find one that meshes with the way your mind actually works, with your background, with whatever.

So that's one way to use this. And then the last point I want to make is just from experience, these are way more fun for me and probably way more engaging if people actually participate.

So I encourage all of you to participate as much as you feel comfortable with you should feel free to speak up.

You don't need to raise your hand. You can unmute yourself and talk. You can also write anything in chat and I'll read it there.

Okay, that's it for the ground rules. The subject for today's is principal questions. In particular, the side of principal questions that are basically just strengthened questions.

If I'm being completely honest with you, these are just strengthened questions. don't, I don't even, I don't even perceive them to be a particular question type.

don't think you could really justify the client that they're in any way unique. They're easy to identify because they just ask the question little differently, but there's no difference between this and, you know, the majority of strength.

It's just identical. But it's still a great topic to go over. It's class is an intermediate topic. I think that's reasonable.

I wouldn't even say it could arguably skew advanced. It's probably not advanced because these are typically not the very hardest strengthens.

But, you know, strengthening is one of the hardest subjects on the test. Yeah, anyway. Okay, but before I dive into this, anyone have any questions about anything we just discussed?

rules, questions about the LSAT, about today's subjects, anything like that? I will give 30 seconds if there are none.

I will dive in. I don't know if being a whiteboard would need to. Okay. Sitting on for now, if anyone changes their mind, go ahead and shoot.

So let's talk about strengthening it, okay? So actually, rather than going at strengthening, you know, directly, I want to talk about this notion of a principle.

What is a principle? What distinguishes a principle from any other claim? Can someone tell me what a principle is?

It's the main point? No, that's definitely not right. It's actually almost certainly not the main point. It's probably never the main point here.

You could in principle have a principle that is the main point, although it doesn't need to be, and it usually isn't.

Actually, the way they're using it here, I think it can't be. I think it never is. Yeah, I don't think it ever is.

Shh. Principle is not another way of saying the conclusion of the art. Okay, well, you guys tried to think of what a principle is.

I just need one second because my cat is streaming back. More so like the premises. They usually function as premises, but that has nothing to do with what a principle is.

A principle is not a premise. Oftentimes, the so-called principle is functioning as a premise, but that isn't what makes it a principle.

That's just an independent fact about it. All right, I'm need you guys a couple more seconds if they don't be right back.

Okay, the kitten was fine, he was just being melodramatic. What's a principle? If someone said it's the principle of the thing.

What are they talking about? If someone stands on their principles, what does that mean? Don't you guys have principles that you adhere to in your lives?

Would you describe yourself? as untrinsabled people? I hope not. What do any of these things mean? They're all referring to the same notion, which is the same thing the else that's referring to.

Okay, core belief. Now we're getting closer, definitely close to a good explanation of some of the usages I've suffered, right?

Truth? I don't think so. necessarily. I mean, one presumably would hope that the principles that they adhere to are true.

They probably believe that, but they don't necessarily have to actually be true. And it isn't the fact that they're true that makes them a principle.

I mean, grass is green. That's true. I don't think that's a principle though, right? principle, whether something is a principle is not about truth.

Okay, actions speak louder than words. Is that a principle? I don't think so. I think that might be a

That's like an aphorism, maybe. It's a saying, it's not a principle. Well, it could be. If you took that to mean, I'm not sure what the principle would be.

Just take action, don't talk. And that's not a great principle, but it could be one. It could be, but I mean, maybe what you mean by that is something like, you should enact your beliefs in your life or something like that.

You shouldn't just say nice things. You should live by them also. the principle might be live by your principles.

It's a funny example of a principle because it's self-referential here for our purposes, but it works. In the face of democracy, you can be guaranteed fundamental human rights.

That sounds, if I'm being really precise, that sounds like you're making a claim about democracies, but it's a claim that I've...

makes reference to the existence of a principle probably. I mean, a belief in human rights might be a matter of principle.

The claim that democracy is guaranteed fundamental rights, that would not be a principle. That would just be a claim about democracies.

But we're close. Well, so the most important trait the principles have is they have to be general in scope.

In any government, human rights are guaranteed. I can't tell what you mean by that. The way you're putting it is kind of a little weird.

If you're saying that you believe humans are naturally endowed with fundamental rights and that those rights transcend their context, it doesn't matter if they're recognized by the government.

They're a matter of natural law or something like that, core enlightenment. That sounds like a principle, I agree with you.

If you're making the claim that democracies and governments recognize those rights, that's not a principle, that's just a descriptive fact.

I think you're doing the former, in which case it is a principle. Your wording was ambiguous, but I think I understand what you're trying to say.

Okay, so principles have to be general, okay? So now we need a new distinction, general versus specific claims. What do I mean by this?

What's the difference between a general claim and a specific claim? I'll give a couple examples. Let's do these three.

They won't want to try to either tell me what the difference is in definitionally. Honesty is always rewarded. Truth always wins against odd.

I don't think either one of those are principles. Those sound like claims, at least if I'm taking very seriously the way you're phrasing.

Again, they're aphorisms, they're not principles. There might be a principle working behind that that you were hoping, as a matter of metaphor, I could extract from what you've said, but if I'm interpreting you literally, you haven't stated principles, you've stated claims of the world.

The claim that honesty is always rewarded sounds like just a descriptive claim also sounds false to me. Honesty is very often punished and not rewarded, but regardless of whether I think it's true, it's still just a claim about what happens.

It's not like a principle. Okay. Okay. John, be better. It is specific. It's about a specific person. That's exactly right.

It's just about some individual named John. So this is a specific claim about a particular individual. Precisely right. That's exactly right.

How about, let's go to the bottom. How about lying is wrong. Is that specific or general? General, it's about all the lines, right?

it generally about lying? Not about any particular statement or any particular line. So this is general. How about grass is green?

This one's a little bit weird. It's not that hard, but I guess technically it's a little ambiguous what I mean by that.

But I guess it just depends. There may not even be one answer to this one, but yeah, thoughts about that is a good example of a general claim.

Regular exercise improves overall health. would be a general claim. We're not talking about in one particular. You were a person.

We're not talking about one specific kind of exercise. We're not even talking about one specific kind of health. So it's general in many respects, right?

That's a good example. Yeah, so the two ways of looking at grass is green. Well, it seems general in that I'm, it's at least general in scope as far as what kind of grass I'm talking about.

I'm not talking about one particular blade of grass. I'm not talking about the grass in Ireland. It seems to be talking about grass in general.

So that does seem like probably the right answer. Alternatively, you know, yeah, that's probably just the right answer. mean, that's the right answer.

It depends on the context. If we're trying to talk about like plants in general, then this is a specific kind of a plant or something like that, right?

But if we're talking about like different patches of grass or blades of grass, then this is general. So I guess in some sense, you can for any even claim, you can evaluate.

It's going to, it may be general in some respects and specific in other respects, right? that's fine. Lying is more specific than statements or something like that, I guess.

But yeah. One should always stand for the weak against all odds. That sounds more like a principle. I'm not sure exactly what you're trying to do right now, Rod.

You kind of just keep writing like aphorisms in chat. That sounds like it's probably a principle. Are you trying to find examples of principles?

We're going to be defining it together in a second and giving examples. So we can maybe just, maybe that's more productive to wait for that than guessing, but I mean, okay.

So typically this notion of general versus specific is actually very helpful. Distinction when you're doing logic because broadly speaking, almost all deductive arguments take the following form.

A specific premise, a general premise, and then a general conclusion and then a specific, sorry, a specific conclusion. Okay.

This is the structure of almost every argument. In other words, here's how the most every argument proceeds. start by asserting some specific claim about something you're interested in.

Give a bunch of examples here. Truly the examples are infinite and very easy to generate. But here would be an example.

John lied to his wife. I'm setting out. So that's the specific claim I'm starting with. Presumably, it's something that's usually narrow, descriptive, easy to prove, maybe already widely accepted, maybe strongly there's strong evidence for it or something.

They may not bother bringing it on the test, but it's somewhat right. This is like something we can measure.

Did he lie to his wife or not? he could easily prove this. here he said the following, but here it wasn't true.

And here I can show he knew that. So he lied. Okay. And then I want to, I'm setting out to prove some further claim about John, often one that's

less obvious. John is a bad husband, perhaps. Okay. So the first specific claim is the claim I'm starting with as a premise.

The next one down below is my conclusion. Well, what's strengthening right now. We're also illustrating the point I'm trying to make about the structure of our department.

How lying makes a bad husband?

Yes, lying to your wife makes you a bad husband or something, right? Exactly. Really. And now we've got a valid argument.

More importantly, like I see. Oh, okay, you're taking notes here. Yeah, that's totally fine. If you want, Rod, you can send those notes to me in a private message so that it doesn't quad check for everyone else, but I think it's okay.

It's fine. It's not a big deal. Okay, thanks, Great. And it's good. I'm glad you're taking that sentence. Thank you.

Okay. so not only did you make this argument valid, but notice what it took to do this was a general premise about sort of applying almost like a matter of definition, the concept that was invoked in the specific premise.

So, we start here with a fact about John, specifically the fact that he lied to his wife. Now, what we want to somehow get to is a different fact about John that he's a bad husband.

What's needed is a general relationship between the two facts, so that we know that we're allowed to infer one from the other.

Specifically, in this case, we need the general relationship that lying to your wife makes something. you a bad husband.

Again, what makes you, I mean, makes one, right? So it's universal in scope, it's general. Okay, that's how all arguments work.

Like, look, I can give you, I don't know, Fido is a dog. All dogs are cute. Therefore, Fido is cute.

We start with a specific quam. We know one thing about Fido that he's a dog. We want to be able to reach the conclusion that he's cute.

How do we do this? Well, we need a general premise that relates being a dog to being cute. Oh, all dogs are cute.

Well, now it makes sense. That's how I'm able to deduce that Fido is cute from the fact that he's a dog.

All carrot, you know, how about this is a carrot? All carrots are This is a vegetable. We went from the coin that this is a carrot to the coin that is a vegetable.

how did we bridge that gap with the assistance of the general? for all premise that relates to two. Okay, basically all arguments need the structure.

Now they can get more complicated. You can add more premises. can futz around. But usually these all just amount to slightly more complicated ways of building this basic framework.

Okay, this is also a really easy way to tell what's missing from an argument. And it's always gonna be the principle that's missing.

It's never the specific claim. Okay, so I care. Suppose I gave you the following argument. Okay. All right, so this is just a classic strength and with sufficient premise, which by the way is very, very, very similar, arguably identical to strength and principal strength.

So again, almost always identical. So what's the answer here? I'm not going to give you multiple choice answers. I want to just solve this thing.

This is like practicing anticipating, but these you can anticipate unbelievably precisely. Very, very, very, very sharply, if you know what you're looking for.

Actually, I want to give you guys time to do this and I tend to get antsy. So here's what's going to happen.

I'm vanishing into the night. I'm abandoning you. I'm the father that went out to get a cigarette or whatever the meme is and never came home.

I'm just I'm gonna step away for 30 seconds to get some more water and then when I come back, I want you guys to tell me what you think.

Okay, feel free to argue amongst yourselves and chat or, you know, conspire anything you want. You guys can work together group project.

Don't care. Okay, good luck. You You Okay. All right, where are we going? Have we made progress? I'm not seeing a lot of collaboration here.

I see rags trying to collaborate. Okay. Anyone want to speak up? What's the answer? How do we fix this argument?

it.

So there's no currently there's no correlation between sorting trash better. And how it will help the environment and save the taxpayer money.

So that's not true.

That's the only thing you do have. I didn't explain the mechanism that I don't need to. I'm telling you that if the law passes, it'll help the environment to save the tax for buying.

So the only thing you do have from this argument in the premises is the guarantee that the law will have those two consequences, right?

I didn't justify this to you, but this is a premise. don't need to justify this. This is just a premise.

This is where I'm starting from. You might disagree with this, but the test doesn't care whether it is irrelevant on this test, whether these claims are true.

First of all, I don't know what it would even mean to say that you're not sure this is true.

is a fictional law in a fictional town. I don't know what the basis would be for anyone thinking that this is true or false.

We have no evidence, but regardless, we don't need it. I saw a hand up. I'm sorry, but then it also went away.

Did someone else want to speak? over to raise your hand. You could just speak up and also feel free to interrupt me.

Yeah, it was me. I was thinking, so the second sentence we have like a premise that says, if the new law passes, it will help the environment and save the taxpayers.

So an answer shows that would make sense of something that kind of like shows how the environment got better, or shows how much students or how much like taxpayers saved.

No, you're making the same mistake that that everyone else here was making. That's not missing Wait, I don't I don't need to I don't need to explain how this is gonna happen or why it's true I this is my premise the wall will have these consequences.

That's the only thing you know about this wall, right? In fact, the only thing you know about this loss is it's fictional anyway is that it's gonna help the environment and save the task Better money.

That's not a logical flaw in this argument. That is in fact the only thing the argument does have Basically, not if you have to figure out what's missing.

go for it Trash better or penalty of fines like I don't know the sentences Sort their trash better or pay penalties All the fines is that what you meant?

Yeah, what it means to be on penalty of X is if you don't Then you could be fine. That's what this implies now So you and Fatima also had a similar idea there so you both said well is the missing assumption that citizens will comply with the law

off. But again, that's not relevant. I don't know whether they're going to comply with the law. All I know is whatever is going to happen, it is a matter of assumption here that the result will be that the environment has helped and that taxpayer saved money.

I don't know if that's because everyone's going to comply with the law or they won't, but these good results will happen anyway.

Regardless, the one thing, back to the only thing asserted as premise in this argument, is that you'll get these consequences.

It doesn't matter how, why, and not that that is relevant to the logical force of the argument. By the way, even given this, it's not a good argument.

This is a bad argument, but you guys haven't figured out why. It doesn't just matter. I think he may have seen this before for me.

I'm not sure. So if he's seen this before, he has to be careful. You guys are reminding me a little.

still have this many times. you were reminding me of a bull in a bull fight. charging at the red flag.

only thing you want to fight with is the only thing they've given you, but this argument is bad as all arguments are as a matter of logic, not because of what it's given you, but because of what it hasn't given you.

You're looking for the gap in the logic, and instead of doing that, you're all charging headlong into the premise.

The premise is not happening to fight with, right? Go for it, Catherine.

What's up? So what will happen if the law isn't passed?

Well, that's an interesting suggestion. Okay, why might that matter?

Because it may strengthen the argument of why the law should be passed.

So yeah, but wait it out. Show me how. Give me a scenario where this argument doesn't seem good because of potentially what you've written.

If you think it's relevant, explain to me. Show me why it's relevant. Citizens will want to pay attention to a law unless there are consequences or fines given.

That's not necessarily the subject of that, but again, I don't even know whether citizens are going to pay attention to this.

I have no idea. This is just irrelevant. All I, whatever they're going to do, the law is going to have two, let's be a little more direct.

Okay, let's just summarize what we have. We have only one press. This law will have two specific consequences. What's the conclusion?

What's my conclusion here?

That the new law should be passed.

The law should be passed. Where's the gap in the reasoning? Remember, nothing that isn't explicitly stated can be assumed.

Anything you're assuming on behalf of half of this argument to it, anything you are thinking in your mind that explains the supposed relevance of the premise needs to be spelled out or it is an assumption that the argument depends on.

There are a number of assumptions here. There is one premise we can supply that will make this formally valid, but we can also just call out some of these assumptions.

Do you just talk to your money and say it in for a money plural?

Well, I mean, it seems like it's got to. It's basically the only premise to have that in the environment.

So look, if I just told you, suppose, let's go down here, completely away from the conflicts of this argument.

Suppose all I said to you about a law that you've never heard of, you don't even know what it is or what it does.

All I did was tell you it will have two consequences. I didn't even specify what they are. And then I go, so we should pass it.

What needs to be true for this to make any sense? No, whether or not the majority will vote for it is not relevant.

I didn't say they will pass the law. I said they should pass the law. It relevant. By the way, I don't even know if this is a majority vote or not.

I have no idea. You're making very specific assumptions about procedure, but even if they were true, it would have no bearing on the question at hand.

The question is not what will happen, it's what should happen. If I just told you, this thing won't have two consequences, therefore we should do it.

Forget the laws. Hold on. This, you're not talking about what to do with your friends. Go for it. would you say?

I'm sorry. didn't mean to talk over you.

Yeah, yeah. Sorry. The two consequences have to be positive.

Yeah, that's good. These better be good consequences. Let's now add that. If this isn't true, then this would be a good example of a required assumption.

Right? These aren't even good. Good things, then this is a crazy argument. But is this a valid argument now?

Where are we good? Is that all we need? Ah, Joseph gave the true answer to the other question. But before we double back on that, let's just stay here.

Is this enough? What's missing? There's still a whole heck of a lot of stuff missing, okay? What else is missing?

A general premise?

Well, yeah, that would have been even more helpful before, probably. But what does they call it? All you know is a wall of two consequences, and they're both good things.

Is that a good enough basis for concluding that we should do it? Like, no, you would need to know if there will be any negative consequences that will happen positive?

Excellent, okay. So the other key assumption is there are no unspecified negative consequences that would outweigh the positives, right?

So really both of these assumptions were missing from the original argument. Let's go back and look now. All we said was that the law would help the environment and save the taxpayer money.

We never even said that those were good things. Now, intuitively, they are, but that's an assumption. But more importantly, we never said anything about what else the law is going to do.

Okay? What if the law is unconstitutional? What if the town is in Texas and the people are going to get so pissed off that the government is telling them what they do with their trash that they're all going to like march on the local city of Holland, burn it down?

There are no unspecified consequences. I don't think that's a required assumption. They're almost always unspecified consequences. The relevant assumption is that there are no unspecified consequences so negative that they'll outweigh the puzzles, right?

I'm sure that there's always nearly infinitely many unspecified consequences to everything, right? only question is, are there ones that are significant enough?

Now, we have to double all the way back there because nothing we've said quite answers my question. I asked for a single assumption that would allow the argument to be properly drawn.

That applies would be formally valid as matter of logic. We've listed two sort of considerations that need to be addressed.

How can we address both of these at once and create a valid argument with one missing premise? Admittedly, the right answer is already a chat, but I still want to see if someone else can understand why it's a

answer. Catherine, was it you who said we need a general promise?

No, that was it me.

It was not you. Oh, was it? I don't know. It was me. It was you. was you. What should I call you?

Probably not Richardson, but you could say effect trying to convey.

Eva.

Okay.

Oh, I see there's a comment after Richardson. Oh, I'm stupid. I'm sorry. I don't know what my brain was like, misfiring terribly.

I bought it. So, Eva, yeah, so you said we need a general premise. Well, that was true. So now let's use that insight.

Because look, we have a specific premise about what the wall will do. And then the conclusion is another specific claim about the law.

We want to somehow go from the fact that the law will have these two consequences to the further fact that it should be passed.

Can we connect the dots here? What's missing? Give me a general relationship that will allow us to move from one to the from the premise.

to the conclusion.

Maybe these two specific consequences are beneficial?

That's half of it. That's certainly part of it. But I don't, my conclusion wasn't that the law would be beneficial.

My conclusion is that it should be passed. So it should be as specific as possible. Literally, play connect with us.

True, Joe, you're making a good point there. If they asked for a required assumption, there are, in principle, infinitely many possible answers.

There are a lot of required assumptions. Of course, the big ones are that these consequences are beneficial. Another big one is that there are no negative consequences that would outweigh them.

But there are a million other required assumptions. you're saying, it's possible to even have certainty about the consequences of an action, that it's, you know, I don't know.

I mean, you could get more gram or not, philosophy gram or not, so you're willing to get about this.

You can start listing of the Gillian required assumptions. of everything, right, that laws are an appropriate object for normative consideration, that yada, yada, That consequences are relevant to the normative status of a law, and so on and so forth.

But I want to stick with the court once here, because there are some very significant gaps that you guys need to be able to see like this.

There shouldn't be no hesitation. You should look at this, and instead of getting dated to worry about the truth of the premise, which is no one cares about on the test, you should instead go, okay, hold on.

They just mentioned some consequences and then concluded a should. They're missing the assumption that these things are good and they're missing the assumption that there are another bad things going on.

Those two should come out fast. Now, I'm gonna, you guys see what Joseph said earlier in chat. This is the right answer, good.

missing premise, if you want to make this about what argument is, any law that would have the these two consequences should be passed.

Yeah, possible, what you said is a necessary assumption. It's not enough though. It's not a sufficient assumption. adding the assumption that it wouldn't introduce significant costs does not on its own make this a valid argument.

I still need to know that these are good things, right? But you're right, now you're on a very good track here.

That is a significant problem. So something like this is the missing general premise. General because it should be universally scoped across all laws, any law that would have these consequences should be passed.

That's the assumption they're making. Now, to be clear, this is not a reasonable premise. This is an unreasonable claim.

And I'm not surprised that it's an unreasonable claim because this is an unreasonable argument. It doesn't matter whether the assumption is reasonable or not.

They didn't ask for a reasonable assumption that would allow the argument to be properly drawn. They just asked for any assumption that would have

while the argument we've probably drawn. This is an assumption that when added to the stated premise makes for a valid argument.

OK, this is what you need to learn to do. Well, you don't need to quantify anything. You just need to bridge the gap between the premise and the conclusion.

This actually is a task does not require a lot of brain activity. This is actually very, very, this can be a very brain dead task, truly.

It is literally a game of conductodonts. Here's what I did to get the answer. I looked at the premise.

They only gave me one. Here, I'll write it out more explicitly. This law will help the environment and save the taxpayer money.

That's what the premise said. I just wrote it down word for word. They didn't give me a second premise.

And then they said the law should be passed. Step one. Well, I have a specific claim about this law and then a specific conclusion about this law.

Got it. I know what I'm missing. This is what you said. I'm missing a general premise. And I know what the general premise has to be about.

It needs to be a general premise about this law. Sorry about laws in general. And I know where it needs to take me.

It needs to take me from here to here. Oh, sorry, you guys can't see my highlighting. It needs to take me from here to here.

Right? It is literally a game of kakadots. The general statement is if help environment If help environment and save money, then should be passed.

That's all that's missing. No thinking required, I don't need to endorse this, I'm just trying to identify what it is that the argument is assuming.

And now we can fill it out with grammar. For a while would help the environment save money, to tax their money.

Then that law should be passed. And now we've got a valid argument. Is there also missing connection between the trash sorting and the consequences?

So interestingly enough, the version of this argument, they give more than one version of this of this argument is given as a real LSAT question, but the wording is slightly different.

They don't say, they don't word the premise this way. They word it more weak. They say if all citizens, if the citizens started to sort their trash better.

Then it will help the environment and save the taxpayer money. If I had said this, then there would be an issue.

How do I know citizens are actually going to start to do that? Now I'm going to worry about compliance and enforcement.

What if they're just taking the fine instead? Now we've got problems. But I worded it to avoid that. I just said, if the law passes, then you don't have to worry about enforcement or anything like that.

Now, I understand you all have an intuition here. And in some sense, it's understandable, but it's simple, it's wrong.

But your intuition is, well, how do we know this is true? What's the right answer to that question? They didn't justify this.

So how do you know this is true? Let me show you why that's a very, very bad question. Remember when I gave you this argument?

Fido is a dog, all dogs are cute, therefore Fido is cute. How do you guys know that Fido is a dog?

How do you know that's true? Anyone who thinks it's a reasonable point to ask, how do know this is true?

Okay, how do you know Fido is a dog? No, there's no one less to that. There is no one less.

There is never a time in this test ever when you're expected to wonder about the truth of a premise.

It makes no sense. These are literally all fictional scenarios. There is no truth of the matter as to whether this new law will have these consequences.

This town doesn't exist. I don't know where it is. It's not it's it's in fictional space, right? Who is Fido?

I have no idea if Fido doesn't exist either, okay? It's Fido and there's no answer to that question. It may not even be a coherent question.

More importantly, it is totally irrelevant to the question being asked. Whether or not an argument is formally valid as a matter of logic is strictly independent of the truth of the premises.

Validity is a formal relation. Validity is defined in the following way. An argument is valid if the conclusion, the truth of the conclusion, is necessitated by the truth of the premises.

That's a relation that holds independently of whether the premises are true. The question is if the premises are true, would the conclusion also have to be true?

That's the only question that we're asking. The purposes could be false. It's not relevant. So, when you ask me,

How do I know this is true? I don't know it's true, but I don't I don't care whether it's true and the test doesn't care and the question doesn't care It is strictly irrelevant whether this is actually true and in fact given that this refers to nothing It's it's neither true nor false.

It's just it's a prompt So that's not a gap in the reasoning they address this you might you're you're dissatisfied with how thoroughly they've addressed it But actually that shows you're not reading carefully.

They address this. This is the most thorough possible language if then this is an if then This is a this is a sufficiency relationship Simply passing the law is sufficient as a matter of logic to ensure these consequences So this is more airtight of relation than if they had given you 15 premises all of which were like the results of studies That were supposed to indicate that probably the law will have these consequences that would be weaker than this premise

A mountain of evidence, a mountain of empirical evidence would be weaker than this because mountain of empirical evidence would never be an absolute certainty.

But this asserts an absolute certainty if the law passes these benefits will come, right? So you literally can't ask for a stronger assumption than this when it comes to establishing these consequences.

Now, Okay, I'm gonna give another example. I want you guys to see. I want you guys to see how brain dead this process can be.

Here's an argument. Actually, I'm going to write this so that I have no idea if this process is true.

I just have no clue. I have no clue. Okay, that's my argument. Can someone give me a promise that will make this valid?

So, things to keep in mind, there's no premise you could give here that's going to make any sense or be even remotely reasonable, because this is an unreasonable prompt.

This doesn't make any sense. There's obviously no connection between these two things, if they're even true. One is a prediction that no one can reasonably make, given how close the race is.

The other is a very specific claim that I've given no evidence for, that I have no basis to know whether it's true or not, but even if it were true, has no bearing on the prediction.

So there's nothing you can say that would actually be likely to be true that would make sense of this.

Nevertheless, it should be easy as a matter of formal logic to connect the dots. So what's the missing assumption?

Exactly. Yes. Perfect. Perfect. Okay. That was exactly right. If there's a girl dot dot dot. having their right now, then Harris will win.

Dot dot dot. Right? That's it. OK. Essentially, as a matter of logical structure, if you want it to be formal, all this nonsense just amounted to the first premise was just some claim A.

And then the conclusion was just some further claim B. What was missing was a conditional statement. If A is true, then B has to be true.

Once added to these otherwise irrelevant claims, now the argument flows. Ta-da. That's all you're expected to do. That's all you're expected to do on every single strength and with sufficient premise question on this test.

I can't. I don't think I've ever missed one of these questions in my life because this is all you need to do.

And these are considered one of the hardest question type that there is that has an unbelievably low hit rate.

But that is all you need to do. But technically, it's 2PM. But I started a little late because we were chatting.

So I'm going to stay over for another five minutes and I'm actually going to pull up a question on the website.

Well, I'm doing this and we're going to solve it. I want you guys to think of you have any other questions too about anything, because I'm happy to address that.

But first I want to, I'm going to, I'm not cherry picking this question. Okay, I'm just going to pick a random question now.

I'll show you how randomly I'm picking. Okay. Okay. Never done this one before. This is the first one in the list.

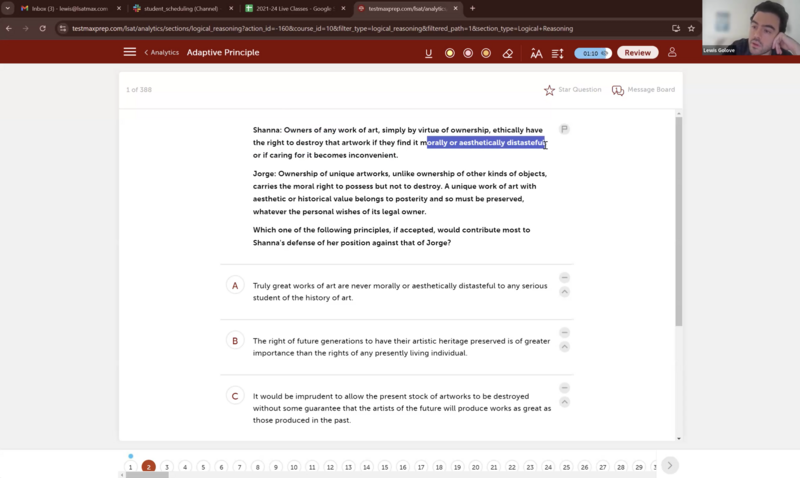

Owners of any work of art simply by virtue of ownership ethically have the right to destroy that or work if they find it morally or aesthetically distasteful.

Or if caring for it becomes inconvenient. Okay. So this is like a conclusion that you haven't bothered to argue for yet.

but we're going to look for, okay, looks like we're going to eventually have to defend it. Okay, so George is about to attack it.

Ownership of unique artworks, unlike ownership of other kinds of objects, carries the moral right to possess but not to destroy.

Okay, so this is the difference in their views. Shauna thinks ownership gives you the right to destroy, although she didn't say it for any reason.

She specified some reasons. She said it gives you the right to destroy if you find it morally or aesthetically distasteful.

That's pretty broad, but still it's not for any reason. For instance, she didn't say necessarily that you could do it because the day was an odd number date in the month of August.

That wasn't a reason that she listed as sufficient, but this is still quite broad. Morally or aesthetically distasteful, and then she says or if caring for becomes immediate, now it's even broader by a lot.

Okay, but George denies this. George says it does not ownership does not. confer the moral right, uh, to destroy.

And then it seems to both be talking about morals here, ethical morals, so that's the same. Now, he does specify that he's only denying his claim in the context of unique artworks.

A unique work of art with aesthetic or historical value belongs to posterity, and so must be preserved. the personal wishes of his legal honor.

So he says, there's actually two caveats here. If an artwork is unique, oh yeah, go ahead, I'm sorry. Yeah, do you have anything to say?

I thought there might be a comment. If anyone has a comment, feel free to speak up. Don't let me talk over you.

Otherwise, I will continue here. Okay. So he says, with two caveats, if a work of art is unique, and if it has aesthetic or historical value, then ownership does not convey the right to

destroy, because it belongs to posterity. Okay, now we're looking for a principle, if true, in other words, a missing general premise that would defend China against George.

Well, we can basically see the outline here. Maybe a claim that whatever interest posterity has in a work of art is weaker than the personal property right, something like that.

I don't know, let's take a look at how they're going to phrase things. not sure how they're going to do this.

Truly great works of art are never morally, oh, I see, never mind, they're looking for compatibility here, actually. Potentially.

Well, this is not helpful, though, because it has too many caveats. Any serious student of the history of art.

I have no China's principle was broader than that. So I don't think this is sufficient to defend your principal.

She's just talking about any owner. I don't know if this this only applies to serious students in history. Also, it's only partial because she also wanted the right to destroy in case of inconvenience.

Well, B is what I want in reverse. B is a strength in for George here, not for Shana, right?

If the rights of posterity trump all other rights, that's what George seems to me. We need it to be the other way around.

It would be imprudent to us, so A and definitely. It would be imprudent to allow the present stock of artworks to be destroyed without some guarantee that the artist of the future will be.

This, again, looks like a weekend, not a strengthen her position. She wants to allow destruction. There are certain entities over which no one would be ethically justified in claiming absolute rights to ownership.

Again, this seems like a weakened her position. Although, if no one could claim absolute rights, that might undermine the strength of posterity's claim, but that's just like this seems like a bad answer.

Okay, good. I see a vote for E. I'm glad to hear that because everything else has looked terrible to me.

The autonomy of individuals to do what they wish with what is theirs must not be compromised in the absence of threat.

Well, there you go. This leads to the conclusion that whatever rights posterity has are are overwhelmed by the private right of ours, right?

Because clearly, in none of these cases, are we dealing with a threat to health and safety? So this just says in the absence of a threat to health or safety, which we don't have here the autonomy of individuals Trump's all So that looks good for Shana.

So it's gotta be okay So I hope this was a little helpful walk through and now since we're over time and I have to run Are there any general questions about anything?

So Sorry, I heard some talking, but I but it cut off we say that one more time Maybe it was a maybe you didn't mean to speak.

I don't know, but if you did I would like to hear it I was gonna say and like these questions is the conditional that always what's missing or soon as it is a different premise It's almost

It's always conditional. Actually, I can show you why that is. It's a quirk of human psychology. It's way too obvious if the specific premise is missing.

Like, if I gave you this argument, like, what's missing from this? Like, this is too obvious, right? It's really easy to apply a principle.

On the other hand, for reasons that I don't understand because I have a freak brain that doesn't feel like everyone else seems to feel, most people don't feel the absence of a principle.

As evidence by the reactions you guys gave you to the examples earlier, right? You didn't feel like a principle was missing.

People intuitively are used to supplying principles on their own. on behalf of speakers. If I said to you, look out, there's a car and you're trying to cross the street.

No one would feel that what I also needed to add was, and in general, it's bad to be hit by cars.

Like, that goes without saying, right? But specific claims don't never go without saying. We're not used to supplying those on behalf of people.

Now, I also just have asked me in a private question in chat here. In general, how trustworthy are the scoring from older tests?

The answer is, they're totally trustworthy, difficulty on this test does not mean if we change. Occasionally, people will make claims to the contrary, but that's also like people make claims all the time about how they can predict the stock market and .

It's basically all , and there's no actual empirics to support any of these claims. fact, the empirics suggest otherwise.

Now, it may be true that law law school applications have gotten more competitive. That's probably true. That varies, but the LSAT itself doesn't get easier or harder as a test to take.

You may have more competition, which may in turn mean that you need a higher score to be competitive at certain schools, but that's a separate question.

Any official graded score chart will give you a strong indication of your performance on the real test. It does not vary.

It's conceivable that there are slight differences in the kinds of questions they ask over time. Most claims to that effect are also wildly overstated, but if we're going back to the 90s, there are real differences between those tests and modern tests.

Not real differences as to difficulty, I would say, but they have slightly different expectations for you as students, but that's a separate issue and not terribly important.

In my view. Okay, any other questions? Seeing none, thank you all for coming and for participating and for letting me be tough on all of you, but I hope it was helpful.

I strongly encourage anyone here who wants to crush this pest to get good at this Connector Dots business. It's super super important and it will help you with a shocking way of