How to Get into Harvard Law.

If you want to get into Harvard Law, take a seat. LSATMax presents our discussion with the Chief Admissions Officer at HLS along with 2 successful personal statements to give you the insight you need to get into a top law school.

Listen to our discussion with the Chief Admissions Officer at Harvard Law School.

Build Your Case for Admission with Confidence.

Personalized strategies to make your law school application a standout.

Learn MoreRead 2 successful HLS personal statements with feedback.

Personal Statement 1

See with a critical eye. Question everything. Never accept anything simply because “that’s just the way things are.” These are the lessons of my past, my present, and my future.

By the early 1980s, life for freethinkers in Iran was untenable. Ayatollah Khomeini, fearful of Westernized Iranians who questioned the authority of his newly formed theocracy, ruled with an iron fist. Dissenters were jailed, disappeared, or, like my father’s oldest brother, killed. As the Islamic Republic became increasingly powerful, government coercion forced the majority of Iranians to accept the new social and political order imposed by the ruthless regime. My parents, however, were defiant and unwilling to accept a life of fear and oppression. Given that my mother is Jewish and my father Muslim, they understood that Khomeini’s new regime would not recognize their marriage. Thus, they chose to leave their life in Iran behind and escape to a new world where they would have the opportunity to live free.

My parents knew that starting over in the United States would not be easy. In Iran, they were well-educated people with postgraduate degrees. When they arrived in California in 1983, they encountered freedom, but it came at a substantial cost. They did not speak English and had no money. They also had two small infant children. To make ends meet my parents found work in whatever field they could; an architect became a gas station attendant and a university professor became a librarian. Having witnessed their sacrifice, I remember asking my father one day if he regretted leaving Iran. He chuckled and said, “No. Not at all. I would rather be a liberated gas station attendant than an oppressed architect.” My parents were willing to give up everything they had for a chance at freedom. At a young age, therefore, I too, became aware of the importance of standing up for your principles, no matter the cost.

Through the lens of my parents’ experiences, I learned that standing up for what you believe does not guarantee justice. Rather, it often results in great suffering. It is not easy to right a wrong. In 2000, shortly after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, my mother was fired from her job as a librarian. It wasn’t that she couldn’t perform her job; she just didn’t fit in anymore. Her termination was clearly a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. But at the time, my family did not have the money to hire an attorney. In the end, she was unable to right this wrong. In 2001, I encountered a similar predicament when I was arrested and falsely accused of a crime I did not commit. With little financial resources, I was unable to spend the money needed to defend myself properly. Instead of clearing my name, I found myself accepting a plea bargain. These two experiences evoked a feeling of helplessness that I never wanted to feel again. It was just a short while later when I encountered yet another wrong. This time, however, I had the chance to do something about it.

Growing up as an Iranian-American, I have always had a deep respect for tradition and it was UCLA’s tradition of excellence that drew me to Westwood. For decades, under the leadership of Coach John Wooden, UCLA’s men’s basketball program, symbolized this tradition. During my first two years at UCLA, however, the program had rapidly deteriorated under the leadership of head coach Steve Lavin.

Game after game, coach Lavin justified losing with what became his favorite byline: “Our opponent played at a magical level.” To me, Lavin’s words translated to “that’s just the way things are.” Rather than taking responsibility for the team’s failure, Lavin blamed defeat on a paranormal performance by the opponent. Lavin’s reasoning implied nothing could be done differently to change the outcome. I disagreed. Progress comes through change, and if UCLA basketball was to improve, a change in leadership was needed.

I was determined to restore the tradition of excellence to UCLA’s basketball program. To do so, I started a grassroots campaign to “Lose Lavin.” In the spring of 2002, I designed a “Lose Lavin” T-shirt and created a website called LoseLavin.com. The website allowed fans to express their outrage with Lavin by signing an online petition, posting comments, and most important, purchasing my “Lose Lavin” T-shirt, which served as a walking advertisement for the website. It was not long before my “Lose Lavin” T-shirts flooded Pauley Pavilion, and LoseLavin.com became the talk of almost every major sports radio show in Southern California. As the resistance mounted, the athletic department had little choice but to quell the uproar. On March 17, 2003, less than a year after the launch of LoseLavin.com, Steve Lavin was fired.

When compared to the injustices the world faces today, my “Lose Lavin” campaign undoubtedly dealt with a trivial issue. Nevertheless, I learned an important lesson: One person can make a difference. I was just a lowly sophomore in a student body of 36,000, but I rallied the troops and I made a difference. I saw what I believed was an injustice at UCLA and I did something about it. My efforts were not in vain. In fact, just three years after Lavin’s dismissal, the UCLA men’s basketball team made it to the national championship game. Today, UCLA is the #1 ranked men’s college basketball team in the country. UCLA’s tradition of excellence has been restored.

This triumph fueled my drive to be a reformer. Upon graduation, my mind turned back to Iran and problems more pressing than college basketball. Although I was only six months old when my parents fled the country, Iran has nevertheless had a profound impact on my life. Stories from relatives back in Iran constantly remind me of the harsh reality facing the Iranian people. These sad stories inspire me to want to make a difference, to bring about change. Today, Iran is experiencing vast levels of unemployment and underemployment - particularly among the youth. In my honors thesis, I learned that these devastating conditions are the result of the Islamic government’s oppressive economic policies. Researching my honors thesis taught me that jurisdiction in the wrong hands can serve as instruments for not only social and political oppression, but also economic oppression.

During recent work on my newest venture, iAmerica Capital, I have seen a similar phenomenon here in the United States. Relaxed lending laws and an unprecedented period of low interest rates have driven an increase in personal consumption, even though personal income growth is the lowest it has been in decades. The high debt burden coupled with rising interest rates will likely result in a large number of loan defaults in the coming years. This trend combined with recently enacted tougher bankruptcy laws could spell real trouble for a large number of low-income American families. These new bankruptcy laws, by rebuffing individuals seeking debt relief, will make it far more difficult for underprivileged people to escape the cycle of poverty. With this and other injustices, like those seen in Iran, I am not one to accept the status quo or the hopeless pessimism of “that’s just the way things are.”

My life experiences have taught me that the rule of law in the wrong hands can be a powerful tool of oppression. Oppression can only be overcome when people stand up, fight back and do something about it. I want to do something about it. Laws should protect and empower the less fortunate, rather than oppress them further. Today, I look at Iran and see history repeating itself. After eight years of empty promises by reformist President Mohammad Khatami, Iran has returned to the hard-line mentality of the Islamic Revolution. The current climate in Iran is a stark reminder of my parents’ experiences and all they endured to escape oppression. The difference now is I have the opportunity to do something about it. To this end, I seek to attain a legal education, which will provide me with the tools and legal training necessary to go forward and make a difference in this world. After all, jurisprudence is a field of study that is critical in nature, and that which is critical, by constantly challenging the status quo, always has the potential to be better.

Personal Statement 1 - Feedback

If you were to brainstorm a checklist of all the things you’d want a personal statement to have, this one would check off many of those items.

One item on that checklist would be an anecdote about a challenging experience and how that experience informed the person the applicant became. A personal statement doesn’t need to focus on a hardship to be powerful, and personal statements that focus on hardships aren’t always successful. But this applicant’s discussion of their family’s emigration from Iran informs the theme of this personal statement: the applicant’s lifelong belief in “the importance of standing up for your principles, no matter the cost.”

Another item most would put on this checklist is a discussion of the applicant’s goals as a future attorney and the steps they’ve taken to reach those goals. Even though the issue is admittedly “trivial” compared to his parents’ emigration from Iran, the discussion of the “Lose Lavin” campaign checks off this item. This provides a real example of a time when the applicant stood up for what they believed in and rallied supporters, not unlike an attorney rectifying wrongs through a class-action lawsuit.

The last item is a description of why the applicant needs to go to law school to achieve their full potential and future life goals. This statement points to legal issues that motivate the applicant and explains why the applicant wants to use the law as a tool to “fight back and do something about” these issues.

But more than simply checking items off a list, this personal statement tells a coherent story with an identifiable theme. Each paragraph flows into the next, leaving the reader with an undeniable lesson: this applicant’s experiences add up perfectly together to show why they will be a successful attorney, whether they attend Harvard or somewhere else.

Build Your Case for Admission with Confidence.

Personalized strategies to make your law school application a standout.

Learn MorePersonal Statement 2

Tantalized by the sight of the finish line, my legs kicked into high gear as I reached the end of my first Sprint Triathlon to the cheers of onlookers on a hot August morning . Almost a year of training had finally culminated in two exhausting hours of swimming, biking, and running. Even though I competitively ran cross country for seven years, my nerves about this day somehow handily surpassed the nerves about any race I had run during those years. For all the months leading up to the event, I was consumed by a nauseating anxiety that I would fail to complete one of the legs of the race and have to forfeit. Yet I was no longer competing for my school’s team; it did not objectively matter how I fared in the race to anyone but myself. However, the growth I underwent to stand confidently on the morning of the race and accomplish this milestone has a far greater worth than any medal or trophy.

Nine months prior to the race, I could barely swim one length of a pool, capable only of a survival-mode tread . As a child I churned through every swim instructor at my local pool, none of whom ended up succeeding in teaching me a proper freestyle stroke. When I returned home to Naperville after my graduation in December 2022, I was driven back to finish the work of those instructors. Wanting to apply myself to a genuine challenge, I committed to train for a triathlon given my lifelong aversion to swimming. My mom, an avid swimmer since childhood, patiently worked with me through the roadblocks of how to breathe properly and build up stamina for longer swims. The initial physical frustrations eventually gave way to aggressive jitters about the race itself— the fear that my heart would beat too fast and that my breath would escape me consumed my thoughts. In the face of every hurdle, she helped me dispel any doubt that I would not reach the triathlon swim distance of 375 meters. After about six months of incremental improvement, I went from struggling with 25 meters to regularly swimming a full mile.

My training ramped up when I returned to Baltimore to begin my new job at the Office of the Public Defender (OPD) in the Felony Division. Although I highly enjoyed my summer internship and was enthusiastic to continue working there, the gravity of the job seemed out of my depth. In my volunteer work at various shelters throughout college , my and the clients’ worlds intersected only for a few hours per week. I subsequently developed an ambition to contribute more wholly to advancing justice and equity in the city. Working at the OPD has further illuminated the dimensions of advocacy that require an even deeper level of trust and understanding necessary to pursue this work as a livelihood. This was never more apparent to me than when I sat alongside an attorney who, when she left the courtroom following her client’s guilty plea, consoled her client’s grieving family and discussed his sentencing hearing that would follow, where he later received the maximum sentence allowed by the plea.

The flexibility, tact, and empathy the attorney exhibited in her representation both inside and outside of the courtroom floored and inspired me. Sitting in the courtroom and hearing his sentence, . It was clear that neither academic knowledge of the law nor a volunteer background would suffice in enduring repeated devastation and still needing to maintain my composure like she had. But just as in my triathlon training, I feel empowered to forgo what is comfortable and familiar in entering the legal practice through affirmation from my network of support. Through emotionally difficult cases and through technical considerations of how to employ the right case law or elicit the most beneficial testimony, the OPD’s attorneys have given me many opportunities for contemplating my own sensibilities as a future lawyer. In combination with the lessons learned in my years of volunteering and community engagement, I am piecing together the principles that will best contribute to my ultimate goal of being in service to others.

I am now ready to embrace the new challenge of law school, this time with more resilience and an even stronger desire to excel. Having transformed moments of discomfort and defeat into fruitful strides, I am prepared to walk alongside clients in pursuit of their proper treatment and outcomes despite any obstacles. As a lawyer, I aim to bring the holistic perspective that has informed my volunteer work and employment to any clientele I serve. To become the most effective and tenacious advocate possible, I seek an environment where I can engage with people, places and ideas that will push me to think critically and contribute meaningfully. I eagerly await the chance to add a new node of fellow devoted students to my support network, hoping that we can be vulnerable about our lived struggles and assist one another in realizing our potential. At Harvard Law School, I know I will find the tools to continue my lifelong work in progress, steered by my determination and buttressed by those who surround me.

Personal Statement 2 - Feedback

Many applicants hear “personal statement” and think “hardship story.” While a profound story about overcoming hardship can result in a successful personal statement, we loved that Alex's essay illustrated one of the many other ways to craft a compelling personal statement. This essay only touches on two points in Alex's life — training for a triathlon and a courtroom scene — but it succeeds because it’s a cohesive story of an applicant with clear goals and the drive to reach them.

In focusing on these two points, Alex's essay avoids a common personal statement pitfall: the “résumé recitation.” Personal statements that recite each item in an applicant’s résumé can be dry slogs that don’t say anything deeper about the applicant. Alex's essay is anything but that. From the beginning, Alex hooks the reader with evocative phrases like “nauseating anxiety” and “aggressive jitters.” She also gives us a sense of her personality, humorously describing her early attempts at swimming as a “survival-mode tread” and recalling how she “churned through every swim instructor” in her childhood.

Most importantly, Alex's essay conveys that she has the tools, drive, and personality to be a successful lawyer. Alex doesn’t need to say this explicitly in her personal statement — the essay’s two anecdotes show this. The anecdote about the triathlon shows that she can overcome challenges and knows how to push herself to reach hard goals. Her experience in the OPD shows that she has already thought about the impact an attorney can have and has begun working towards a career in public service. Moreover, this part of her personal statement displays her empathy and passion, specifically her desire to provide advocacy based on a “deeper level of trust and understanding” with her future clients. That she cleverly weaves together both stories with the line “my breath escaped me like it once had in the pool” is icing on the cake.

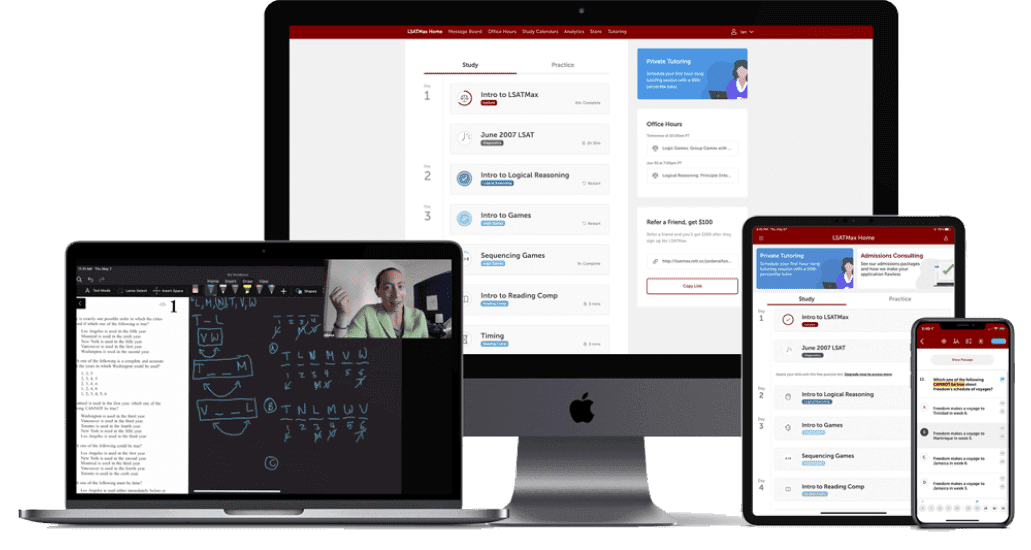

Try the #1-Rated LSAT Prep for Free.

Sign up for an unlimited free trial of LSATMax's #1-Rated lsat course and get access to tons of free content.

It's unlimited. No credit card required.

Become Another Success Story

Kyle Ryman

Texas A&M

+20 Points with LSATMax

150

170

I scored below a 150 on my first practice LSAT in November. In June I took the LSAT and scored a 170. I couldn't have done it without LSATMax.

Callie Ives

Texas A&M

+16 Points with LSATMax

148

164

LSATMax helped me get my score up from a 148 to a 164. I was offered so many full rides which wouldn’t have been possible without LSATMax.

Austin Sheehy

University of Central Oklahama

+15 Points with LSATMax

155

170

LSATMax is my hero! My starting score was around a 155-158, and I scored a 170 on the June LSAT!

Chris Dinkel

Oral Roberts University

+22 Points with LSATMax

152

174

I went from a 152 to a 174. I'm just excited to have a shot at top end schools again.

Katherine Carey

Emory Law School

+9 Points with LSATMax

158

167

While I was preparing to take the LSAT I was working full time. LSATMax was personalized, user friendly and structured in a way that I could create a schedule that worked for me.

Natalie King

University of Richmond School of Law

+15 Points with LSATMax

151

166

I can't speak more highly of LSATMax. I raised my score 15 points and I know that I got into law school because of LSATMax.

Jackson Minasian

Cal Poly

+13 Points with LSATMax

154

167

I tried LSATMax after my attempt with the $950 Testmaster's online equivalent brought my score from a 154 to a 158. LSATMax was different in all the right ways.

Davis Metzger

+12 Points with LSATMax

159

171

The tutors at LSATMax were a godsend. They took me from a 159 to a 171 on my LSAT. I wouldn't have been able to get my score up without them.

Jordan Birnholtz

+23 Points with LSATMax

148

171

LSATMax helped me raise my score from a 148 diagnostic to a 171 in seven months. I'm thrilled with that outcome. LSATMax's tutors were exceptional.

Alexandra Mathieu

+12 Points with LSATMax

146

158

The program itself is massively helpful from having the actual books in front of you to having the entire course in an app. LSATMax is the reason I am going to law school this fall.